Sabbath Wisdom for a Post-pandemic World

Sabbath Wisdom for a Post-pandemic World

Brother Sam SSF reflects on what we might learn from the pandemic about how to live life more slowly, more sustainably, and more enjoyably.

1. Learning to Stop

‘Remember that you were a slave in Egypt, the Lord your God brought you out from there……therefore the Lord your God commanded you to keep the sabbath day’ Deuteronomy 5.15

I wonder how we will remember the time of the pandemic - during which it has seemed that our lives and the life of the world experienced something like a car-crash, brought suddenly to a halt by a great rock in the road, leaving us disorientated, turned upside down. I wonder if we will want to remember it at all. There may well be a desire within us simply to press the re-set button and get back to ‘normal’: to dust ourselves down, put the vehicle back on its four wheels, and continue driving headlong as before. Let’s take up from where we left off, carry on with our business and try to catch up with where we would have been had there not been this inconvenient upheaval. Busy-ness can be a way of coping with trauma.

Yet, of course, the effects of the pandemic will be journeying with us for many years to come – for some a deep sense of loss, for others the bearing of mental and physical scars, for all of us economic and social consequences that we are only just beginning to comprehend. We live with the questions it has raised: What is it telling us about our way of life? What are we learning? How can we live more wisely, more caringly, more gently, more justly in the future?

For the People of Israel in the scriptures and for our Jewish cousins today, the keeping of a sabbath day has been the means of remembering; remembering both the trauma of slavery and also the rescue from out of it which were and are foundational to their life as individuals and as a community. The Sabbath is a time of taking stock, of going back to beginnings, of re-learning the wisdom received during hardship, of recognising and giving thanks for the grace of God which has led and held them. We do something similar on Remembrance Sunday. We do the same when we celebrate the Eucharist.

Perhaps the most important lesson for us to learn from the pandemic is to STOP – to stop, not just when we are forced to stop by a world crisis or a personal disaster, but to stop because it is an essential and integral part of the pattern of holy and healthy living. In a world which has become addicted to accumulating, communicating and getting somewhere - insanely trying to fit more and more into often-over-full lives - the most significant thing we can do on a regular and substantial basis is simply to stop, take stock, remember, reflect - and to give thanks for the grace that has sustained us in these times.

2. Leaving Room

‘In the seventh year there shall be a sabbath of complete rest for the land…….’ Leviticus 25.4

It took just two weeks of lockdown in 2020 for the dolphins to return to the lagoon and canals of Venice, from where they had been excluded by the noise and pollution of the cruise liners and tourist barges which have increasingly occupied their natural habitat over the past decades. The lockdown, which brought a sudden halt to the tourist invasion, made room for these amazing creatures to reclaim their home. We noticed the same sort of recovery in London and other major cities as a result of the reduction of air and road traffic. We were able to hear the birdsong. Sadly, it seems to have been but a temporary human retreat.

St Francis of Assisi told one of his brothers digging over the vegetable patch to leave some space for the wild flowers to flourish and praise God. That may seem whimsical and foolish advice for today’s over-crowded world with hungry mouths to be fed, yet it holds a basic theological and ecological wisdom. The sabbath instruction to leave land fallow every seventh year allows room for recovery of the soil. It also acts as a check upon the hubris that it’s all there for us – a giant warehouse of stuff for human exploitation or a playground for our entertainment. It’s a reminder to us that the land doesn’t belong to us but, rather, that we – even those of us who live in densely populated urban areas - belong to and are dependent upon the land and all that it contains.

During the lockdown the opportunity to walk in local parks, to discover urban greenways or to get out into the country has been a lifeline for many; it has given us breathing-space. If we humans are to continue as a species, we will need to safeguard that same breathing space for the other creatures with whom we are essentially bound up.

In a world which is already experiencing the catastrophe of a mass extinction of species, which in the end will be catastrophic for the human race as well, it is essential for us to re-learn a sabbath mindset; a hospitality which leaves room for the ‘other’ – for the weeds in the pavement, for the microbes that are essential for healthy, productive soil, and for the homeless person squatting on the pavement. In John’s gospel Jesus tells his disciples that in his Father’s house there are ‘many mansions’. For the honouring of God’s Sabbath and for our own human survival we also need to ‘make room’ in our common home.

3. Sacred Time

‘You shall keep my sabbaths, for this is a sign between me and you throughout your generations…’ Exodus 31.12

There’s a story of a young man who asks a rabbi, ‘How is it that Jews have been able to keep the Sabbath so faithfully over more than three thousand years?’ To which the rabbi replies, ‘The remarkable thing is not that Jews have kept the Sabbath, but that the Sabbath has kept the Jews.’

The faithful observance of the seventh day of the week and has been a spiritual and cultural framework for Jews throughout the generations. It is said that Judaism, since the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple nearly two thousand years ago, has had no great building for worship, but that in its place, through sabbath observance, it has an ‘architecture of time’, a structure that witnesses that time itself is holy.

In fact, all the main world religions have a rhythm of sacred times and seasons. For Muslims, the Friday prayers and the keeping of the holy month of Ramadan are an essential part of Islamic practice. For Christians the celebration of Sunday as the feast of the Resurrection and the following of the liturgical calendar gives a framework to our common life. Even secular culture is shaped by special times, regular public occasions, anniversaries and jubilees: the Cup Final, the Trooping of the Colour, Derby Day and Wimbledon. Some like Mothers’ Day (properly, Mothering Sunday!) and Halloween retain a vestige of their religious origins; others like Glastonbury and The Last Night of the Proms are more recent additions to the architecture of the year.

However, the lockdowns of 2020 and 2021 brought this structure tumbling down. Churches, mosques, synagogues and temples closed for the days of common worship. Public gatherings were banned and even family celebrations had to be abandoned. ‘Christmas cancelled’ ran the headlines in December. Zooming kept us connected but virtual meeting is no substitute for partying, lamenting or worshipping in person. The rhythms of the week and of the year lose their beat if we are unable to mark them with solemnity or celebrate them with festivity. Time in a 24/7 world becomes flattened and community life is impoverished.

Times and seasons with their associations and gatherings, their customs, their special clothes, their music and their food are the building blocks of our cultures. They are ‘givens’ which hold us together and which express who we are and what we are about. They are a sign to us that life is not just a series of one thing after another but, rather, that time itself is blessed and sacred, filled with the grace of God. How we long to recover its architecture.

4. Enjoying the world

‘So God blessed the seventh day and hallowed it, because on it God rested from all the work that he had done in creation’. Genesis 2.3

In a series of mosaics on the walls of the Cathedral of San Monreale, Sicily, which depict scenes from the book of Genesis, the one featuring the seventh day of creation shows God sitting under trees and surrounded by flowers. Some say that God seems exhausted from his efforts over the previous six days, but in my view he looks as though he is simply delighting in all that he has made. Far from walking away after completing the job, God stays in joyful attentiveness to his work, to sustain it and to share his delight. Our keeping of the sabbath is a participation in that delight.

The seventeenth century naturalist, John Ray, said that ‘The contemplation of God’s creation should be part of everyone’s duties on the sabbath’. The problem with the helter-skelter culture which can easily shape our lives is that it doesn’t give much opportunity for such contemplation and for sharing in delight; we pass through the world too quickly, keen to get on to the next thing, the next experience, the next task. And when we do stop it’s often in order to recuperate from exhaustion or to catch up with something that has been left undone. The sabbath, in contrast, has no useful or productive purpose except to be present - to each other, to the world around us and to the gracious Source and Giver of life. Rather than seeing ourselves as the ‘the crown of all creation’ as one of the Church of England’s eucharistic prayers puts it, the sabbath of sharing God’s delight is itself the goal to which we are summoned. In the Genesis story it’s the seventh day, not the sixth, that completes the creation.

It may be that the effect of the pandemic, which stopped us in our tracks, which caused so much suffering, and led to the abandonment of so many of our plans, has been to knock us off our pedestal and to remind us that the creation is not all about us nor our projects for the world. We are part of the whole community of creation, the end purpose of which has next to nothing to do with our possession or control but is, rather, about being attentive to and participating in God’s abundant creativity, overflowing love and joyful delight.

As Christians we believe that this abundance finds its fullest expression in Jesus Christ. He is himself our Sabbath. In the celebration of the Eucharist, Sunday by Sunday, by which we participate in him and are shaped to the pattern of his life, death and resurrection, we are given a foretaste of the ‘never-ceasing sabbath of the Lord’ - which is the sign and hope for a world renewed.

About the author

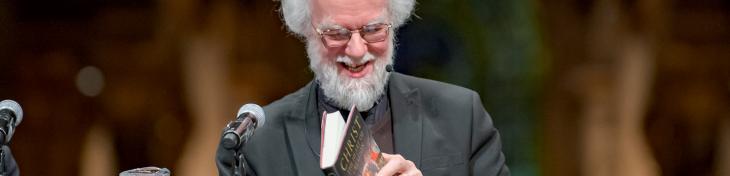

Brother Sam is a Franciscan brother who lives in East London, and was formerly Brother-in-Charge at Hilfield Friary in Dorset. He is the co-author of Seeing Differently – Franciscans and Creation (Canterbury Press, 2021).