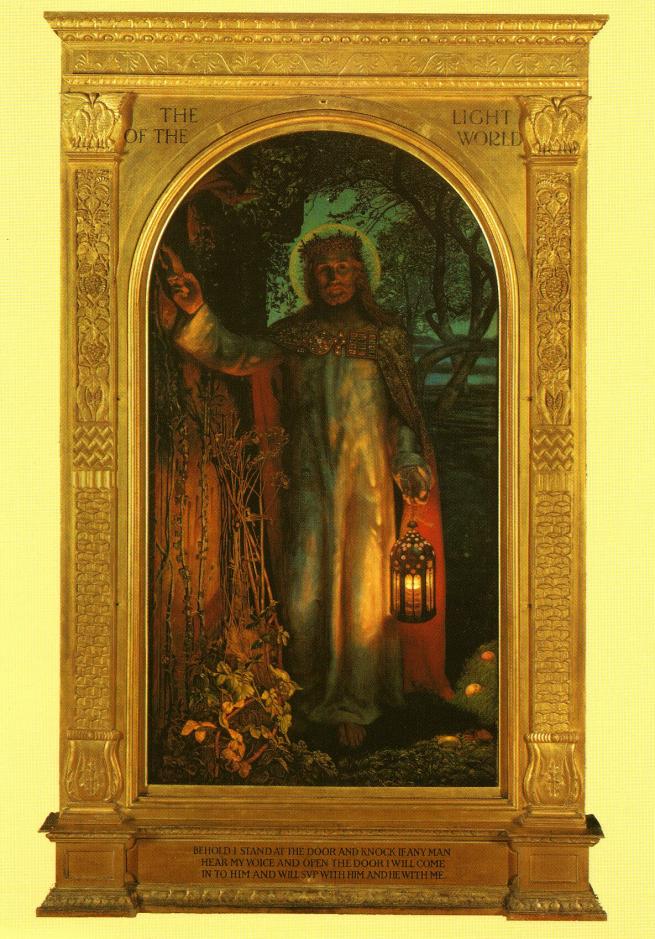

The Light of the World by William Holman Hunt

'The Light of the World', William Holman Hunt, 1900-1904 (Ref. No. 8190).

The Light of the World by William Holman Hunt

Holman Hunt’s painting is one of the most viewed 20th-century art pieces in the world, with a rich tapestry of symbolism to be unravelled.

‘I am the light of the world. Whoever follows me will never walk in darkness but will have the light of life.’ (John 8:12). This verse from John’s Gospel is what inspired Holman Hunt to paint this world-famous image.

This is the third version of this painting by the artist. The first – from 1853 - resides in Keble College Oxford and the second, painted shortly afterwards, can be seen in the Manchester Art Gallery. The piece in St Paul’s was painted around fifty years later, with the assistance of Edward Robert Hughes, and it is thought to be the culmination of Holman-Hunt’s vision.

A painting’s pilgrimage

This “sermon in a frame” is the most travelled art work in history. After it was finished in 1904, it toured the globe, visiting most of the major towns and cities in Canada, South Africa, New Zealand and Australia. Today, it has been seen by millions of people and is one of the best known works of its period.

The painting arrived at St Paul’s after it was purchased from Holman-Hunt by the industrialist Charles Booth and donated to the Cathedral. It was received during a service in June 1908. On that day, the choir sang Psalm 119 which includes the verse: ‘Your word is a lamp to my feet and a light to my path’ (Psalm 119:105).

Layers of meaning

The Light of the World is steeped in metaphor.

There are actually two lights shown in the picture – the lantern, which is the light of conscience and the light around the head of Christ, the light of salvation. The door represents the human soul: its lack of handle, the rusty nails and its hinges overgrown with ivy are intended to show that it has never been opened – and the figure of Christ is asking for permission to enter.

The morning star appears near Christ – the dawn of a new day – and the autumn weeds and fallen fruit, representing the autumn of life. The writing beneath the picture is taken from Revelation 3:20: ‘Behold! I am standing at the door, knocking; if you hear my voice and open the door, I will come into you and eat with you, and you with me.’

The orchard of apple trees is intended to evoke several biblical references. The tree of knowledge in the garden of Eden was – according to legend – an apple tree, and in some Christian traditions the wood of that tree was miraculously saved to construct the cross on which Christ was crucified. The fallen apples could symbolise the fall of man, original sin, and sometimes in Italian art can refer to redemption. Neil McGregor, Director of the British Museum, has noted that in the painting Christ not only knocks at the door; he is himself the door.

The frame

The extraordinary Renaissance style frame which surrounds and supports the painting is the work of two female artists: Hilda Hewlett and a Miss Smith, her anonymous co-creator.

Hilda was a passionate craftswoman, and once vowed to ‘never be without some object or interest of such importance that all discomfort, annoyance or temporary misery counted as of quite secondary consideration’. She studied at the National Art Training School in South Kensington and was friends with Holman-Hunt’s daughter, Gladys. Together they had made a cassone (or Italian marriage chest) using many of the same materials as are used in the fame: wood; gesso (a mixture of chalk, glue and white pigment) and gilding. Hilda wrote that the frame was ‘a work of months of patience, not only because it was a very long job, and though Holman-Hunt knew what he wanted, his sight was not good, his sketches were too vague for words: no – not for words, but for carving’.

Later in life, Hewlett defied her husband by becoming the first British woman aviator to win a pilot’s licence. When they separated in 1914, she was working intently on her successful aircraft manufacturing business.