Tyndale's New Testament

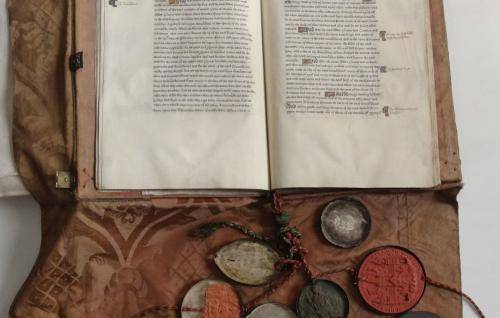

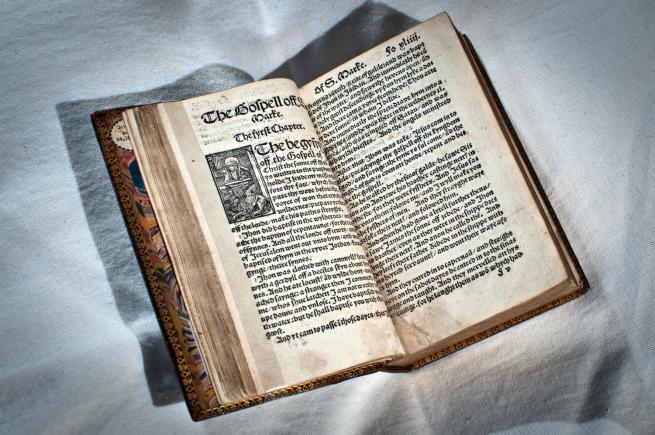

William Tyndale's New Testament, 1526.

Tyndale’s New Testament

One very small book housed within the library of St Paul’s continues to exert its influence on us – almost 500 years since its contents were nearly wiped from existence.

Measuring just inches, the Cathedral’s first edition of William Tyndale’s New Testament – the first ever holy book printed in English – is one of just three copies that remain in the world today.

William Tyndale was a scholar and priest, but also a man who dared to challenge. Educated at both Oxford and Cambridge, Tyndale was a controversial advocate of 'personal faith' – the idea that a person should be able to have a relationship with God without the established Church getting in the way.

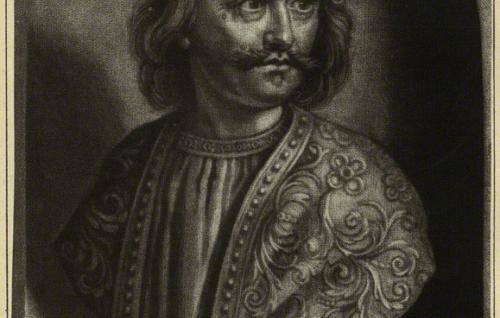

A woodcut print of St Mark from Tyndale's New Testement.

At a time when King Henry VIII's rule over England was absolute, Tyndale’s decision to take on the might of the monarch by translating the Bible was bold. In 1526, the publication of his New Testament made it available in English for the first time, and helped to bring continental Reformation ideals to the people of England.

Making the Bible accessible

By writing the Bible in English, Tyndale was giving all people, 'from princes to ploughboys', the chance to experience first-hand the word of God. This empowerment of the everyman threatened the tight rule of those in power, who set about tacking down both the book and its author.

Tyndale wrote that the Church authorities banned translations of the Bible in order "to keep the world still in darkness, to the intent they might sit in the consciences of the people, through vain superstition and false doctrine...and to exalt their own honour...above God himself."

Inspired to push ahead with the forbidden translations and get the Bible into the hands of the people, Tyndale had to travel to Germany – the centre of the Protestant Reformation under Martin Luther – to start printing. Betrayed, he was forced to move on to Worms and from there many copies were smuggled in to England to be read in secret. Any copies which were discovered by the authorities were burned in public, many of them at St Paul's Cathedral in a campaign led by the Bishop of London.

Living increasingly close to the edge, the authorities eventually caught up with Tyndale and he was executed near Brussels, Belgium, in 1536.

A lasting linguistic impact

Although Tyndale was captured and executed and his book mercilessly burned, the power of his words lived on. Within his tiny book are words and phrases which have gone on to influence the world, and continue to do so. Roughly 80% of the King James New Testament used today is Tyndale’s work.

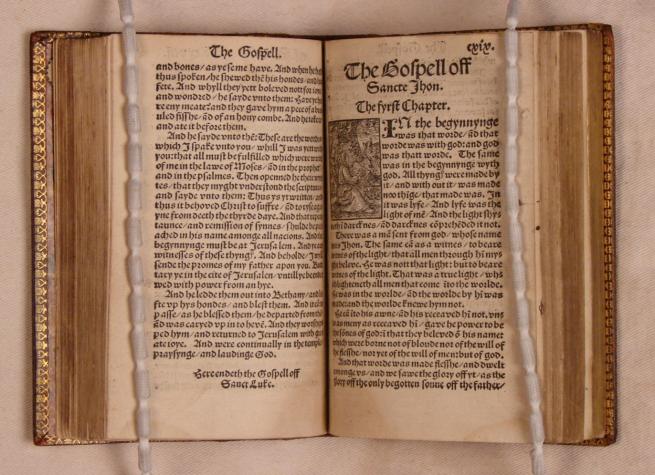

The Gospel according to St John.

It is still greatly admired for the clarity of the writing, and a surprising number of Tyndale's phrases are still in common use today. These include:

- 'under the sun'

- 'eat, drink and be merry'

- 'signs of the times'

- 'the salt of the earth'

- 'let there be light'

- 'my brother's keeper’

- 'lick the dust'

- 'fall flat on his face'

- 'the land of the living'

- 'pour out one's heart'

- 'the apple of his eye'

- 'fleshpots'

- 'go the extra mile'

- 'the parting of the ways'

- ‘broken-hearted'

- 'eat drink and be merry'

- 'flowing with milk and honey'.

In spite of the efforts to hunt down and destroy all copies in existence, three survive to this day. The St Paul's copy seems particularly defiant, as it is now kept on the site where the others were destroyed.

Today, Tyndale's tiny book is the greatest treasure within St Paul's library collection. However, in keeping with its earlier contraband status it arrived in the Cathedral surreptitiously – its true nature was unappreciated when it was acquired in 1783. The leaves of the Gospels and epistles had been deliberately intermixed to disguise the contents of the book, should it have been discovered. In the 19th century the sheets were rearranged in proper sequence and the volume was rebound.

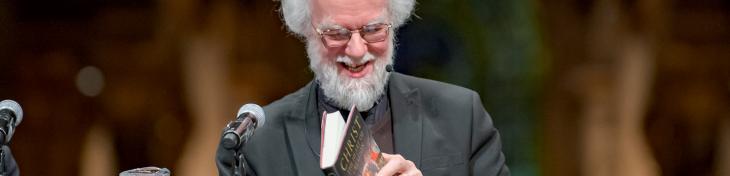

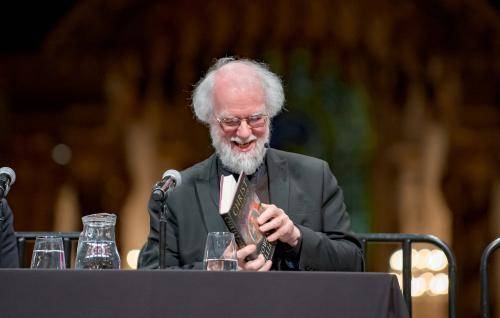

Podcast episode:

William Tyndale’s New Testament

Our podcast series Stories from St Paul’s, produced and presented by Douglas Anderson, explores over a thousand years of Cathedral history. In episode 7 of series 2, Douglas explores the way Tyndale's translation challenged established religious and political power and authority.