Our timeline

Explore our timeline

- 604 - 1500

Early foundations

- 1501 - 1666

Reformation and revolution

- 1667 - 1711

Rising again

- 1712 - 1935

Memorial and celebration

- 1936 - today

An international emblem

604: St Paul's is consecrated

Very little is known about the site and origins of St Paul’s Cathedral. We do know that, in the years after Christianity was adopted as the official religion of the Roman Empire, a cathedral existed in Londinium, and was at one time the seat of a Bishop named Restitutus.

At the end of Roman occupation, there was a significant gap between the departure of the last British bishop and the arrival of a new mission from Rome. In 595, Pope Gregory the Great chose the monk Augustine to lead a mission from Rome to convert the pagan Anglo-Saxons to the Christian faith. Augustine founded Canterbury Cathedral – becoming the first Archbishop of Canterbury – and set about the conversion of the East Saxons, whose capital was London. Gregory sent further missionaries to support Augustine’s mission, including Mellitus, who was consecrated Bishop of London in AD 604.

Sadly, there are no physical remains of the original Cathedral structure, nor are there any records or descriptions which would enable us to depict it accurately. The Cathedral stood until 1087 when it was entirely consumed by fire – or so damaged that it was unfit for worship. Mellitus was only Bishop of London for as long as he had the support of the King, Ethelbert. The religious destiny of the kingdom was constantly in the balance, with the Royal family itself divided among Christians, pagans, and some wanting to accept both. When King Ethelbert died and was succeeded by his pagan son Eadbald, Mellitus was forced to flee, first to Canterbury and then to what is now France. After Eadbald converted to Christianity, Mellitus returned to Canterbury where he eventually became Archbishop, but he never returned to London.

During his time as Archbishop Mellitus – though suffering from gout – is said to have performed a miracle, diverting a fire that would have consumed a church. After his death in 624, he was revered as a saint. A shrine to Mellitus was built in the St Paul’s Cathedral which stood from 1087 to 1666, and his feast day is still celebrated in the Cathedral on 24th April each year. After Mellitus was driven out, there was no Bishop of London again until a Northumbrian missionary named Cedd became bishop in about 653. However, the Christian presence in London had been established and – other than during Scandinavian occupations – St Paul’s Cathedral would remain a Christian site for good.

1240: Medieval 'Old St Paul's' is consecrated

In 1240, the medieval Cathedral – what we call ‘Old St Paul’s’ – was consecrated -the act of declaring a church sacred.

Construction of this Cathedral started in 1087, following a fire which destroyed the previous Anglo Saxon Cathedral. This new Cathedral would suffer similarly bad luck when it came to disastrous events, meaning it was not completed until 1314.

It was Maurice, Bishop of London, who had the ambition to build the longest and tallest Christian church in the world. Prior to his time at the Cathedral, he has been William the Conqueror’s chaplain, and succeeded in persuading King William to donate stone to the building project, some of which would come from Caen, Normandy. Although Maurice died in 1108, successive Bishops of London – and monarchs – each influenced and financed the Cathedral’s continued construction. King Henry I (who reigned from 1100 – 1135), for example, donated more stone and commanded that any material for the Cathedral travelling up the River Fleet should be exempt from paying toll charges.

Despite support from successive monarchs, a variety of devastating interruptions delayed works over the 200-year building period. In 1135, a fire broke out on London Bridge, which spread all the way to St Paul’s and caused serious damage. Following the Cathedral’s official consecration ceremony in 1240, the still unfinished Cathedral was battered by severe storms in 1255, which caused damage to the Cathedral once more, especially to the roof.

However, once funds were secured to make the necessary repairs, Old St Paul’s expanded again, lengthening eastwards for the rebuilding of the Quire and Chancel. This meant that an existing parish church on that site – that of St Faith – was demolished to make way. The church parishioners were afterwards allowed to worship in the Crypt, where even today there is a chapel dedicated to St Faith.

The final phase of construction was the Chapter House to the south west of the Cathedral, and once finished, Old St Paul’s was at last complete in 1314. It incorporated different architectural styles from Norman Romanesque to Early English Gothic, reflecting the fact that it was the work of multiple architects, bishops and monarchs, and that so many repairs and expansions had been made to it along the way.

Rising from the top of Ludgate Hill, the Cathedral would have been a magnificent and awe-inspiring sight dominating the London skyline. The spire was a whole 38 metres taller than that of the highest point of new St Paul’s (the cross) and its vast footprint stretched out longer and wider than the present Cathedral. Old St Paul’s quickly became the focal point of the religious, political and social life of the city, and for medieval Londoners, a great source of pride: it was their Cathedral.

1505: John Colet becomes Dean

John Colet (1467-1519) was a reformer accused of heresy, who brought his zeal to St Paul’s. As Dean (1505-1519) he transformed the running of the Cathedral and founded the St Paul’s School.

Colet’s enthusiasm for reform made him unpopular with some of his colleagues at St Paul’s, as he frequently called out their failings and demanded better behaviour. In a sermon given in 1512, he called for a church reformation. He believed that the priests of his day were consumed by the prestige they received for being a part of the priesthood, and that many took part in the church only for the hope of riches and promotions. He also accused many of them of participating in the lust for the flesh – feasting and banqueting, vain conversation, sports, plays and hunting – and said they had 'drowned in the delights of this world'.

Colet gave another notable sermon before the Royal Court on Good Friday in 1513. In the wake of political tension, when England was pushing for a war with France, Colet condemned the potential conflict and prompted Christians to fight only for Jesus Christ.

Colet also viewed education as key to spiritual revival, and personally secured an endowment from the Mercers’ Company to re-establish St Paul’s School. A new building to house the school was completed in 1512, to the east of the Cathedral. The masters were given good salaries, and had to demonstrate knowledge of reading, writing and the Christian faith to secure their place. The original stone schoolhouse at the east end of Old St Paul's was rebuilt after the Great Fire, and was again replaced in 1822. In 1884 the school moved to Hammersmith and in 1968 it moved to its current location in Barnes.

Colet died in 1519 and his last will, required that he be buried in St Paul's near the image of St Wilgefortis. His friend Erasmus described his modest grave as 'a little monument', identified by the letters ‘Joan. Col.’. By 1548, he had a more elaborate tomb and in 1575–6 the Mercers’ Company – who had funded the St Paul’s school build – provided a marble addition, removed after the Great Fire of London. Colet is memorialised today in the Deans’ Aisle of the Cathedral with a bust added in 2010.

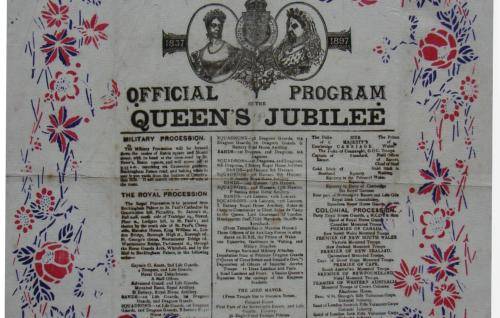

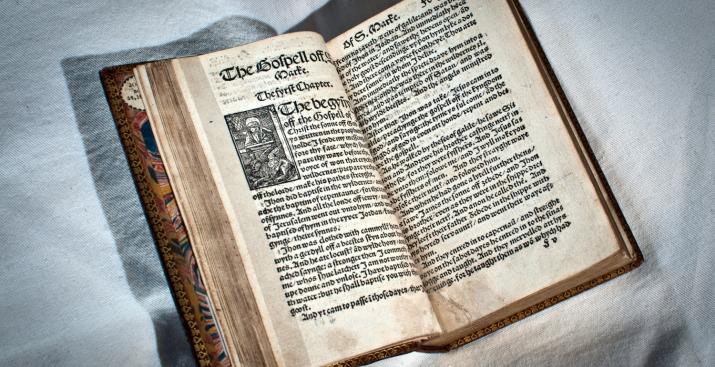

1526: The Reformation

William Tyndale’s 1526 English translation of the New Testament is a rare treasure held in our Library collection.

It is one of only three copies of this translation – Tyndale’s first complete translation of the whole New Testament from Greek – known still to be in existence. At the time of its publication it was shocking and scandalous to many, but the book’s story was also part of a much larger movement in Europe – and later England – at that time: The Reformation.

At the start of the 16th-century, widespread criticism of the perceived corruption and greed of the Catholic Church led to open rebellion. On 31st October 1517, Martin Luther, a German monk and theologian sent his ’95 Theses’ to his local archbishop – a document which protested against the Church’s misconduct. It is also said that he nailed a copy to the door of a church in Wittenburg, but Luther’s main aim was to be able to start a debate in order to reform the Church, and he was not openly critical of the Pope. Without his knowledge, the original Latin text of his theses were translated into German and quickly shared far and wide.

As Luther’s reformist message spread, other reformists began to consider how they could make the Bible more accessible. Scripture, not papal authority, was a key underpinning of Reformation ideas, but as it was written in ancient Hebrew, Greek and Latin, few could read it for themselves. The newly-invented printing press posed a solution, as translations would now be much easier to create and distribute. In England, King Henry VIII was shocked and concerned by the actions of Martin Luther. As a devout Catholic, this led him to write and publish his own theological work called the Defence of the Seven Sacraments in 1521, which in turn led Pope Leo X to give him the special title of Defender of the Faith as a reward for his loyalty.

This loyalty – however – was soon challenged. As the 1520s progressed, Henry VIII became increasingly dissatisfied with his marriage to Catherine of Aragon; they had no surviving male heir to secure the future of the Tudor dynasty. Convinced that the marriage was no longer valid in the eyes of God, he began to seek an annulment so that he could remarry and secure the succession. He had first met Anne Boleyn (who would later become his second wife) in 1522, but it was not until 1526 that he began to actively pursue her.

Henry repeatedly appealed to the Pope to annul his marriage, but the Pope refused. This refusal ultimately led to Henry’s break from the Catholic Church and the establishment of the Church of England. Although Henry remained doctrinally Catholic for the rest of his life, the English Reformation developed along two main lines: the official one – led by Henry as the self-declared head of the Church of England – and an unofficial, grassroots movement of reformers like William Tyndale, who sought to address corruption in the Church and make it more accessible to all.

1621: John Donne becomes Dean

John Donne had lived many lives before becoming Dean of St Paul’s in 1621.

Born in London on the 22nd January 1572, Donne was the third of six children born to John Donne (senior) and Elizabeth Heywood, who was great-niece of the statesman, philosopher and Catholic martyr, Thomas More.

Aged 11, he began studying at Hart Hall, Oxford (now Hertford College) and three years later enrolled at Cambridge University, but never graduated from either. This was because his Catholicism prevented him from taking the oath of allegiance to the monarch, which was needed in order to successfully obtain a degree.

In 1592 Donne went to study law at Lincoln’s Inn, but had left by 1596 for military service under the command of the Earl of Essex. He was part of two expeditions against Spain – in Cadiz and the Azores – and after returning home, went to work for statesman Sir Thomas Egerton as chief secretary.

It was while living in the household of Egerton that Donne met Ann More, who was the niece of Lady Egerton. In 1601 – and against the wishes of Sir Thomas and of Ann’s father – the couple married in secret. This caused a great scandal; Donne lost his job and was even imprisoned for a short time. For the next few years he struggled to find work, and the couple relied on friends and family to support them as their young family grew.

It is thought that Donne wrote poetry from the 1590s onwards, although it is difficult to date many of them exactly. This is because, as a gentleman – a man of higher social class – he thought the idea of publishing for money was beneath him. He was also reluctant to be thought of as a poet first and foremost. Donne mostly shared his works with friends and later, in 1611 and 1612, deeply regretted allowing some of his longer poems to be printed.

Donne also wrote prose pieces on political and religious subjects, and at some point between 1601 and 1615, he became Protestant. Years of doubt about his Catholic faith led to his conversion, and in 1615 he was ordained into the Church of England and made Royal Chaplain to King James I.

In 1617, Donne’s wife Ann tragically died whilst giving birth to a stillborn child. and he vowed never to marry again. Despite this grief, Donne was making a name for himself as a powerful, emotional and engaging preacher, and on the 22nd November 1621, he was installed as Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral at the age of 49.

Donne would continue to write and preach for the next 10 years, sometimes through serious illness, until his death on the 31st March 1631. He was buried at Old St Paul’s, and his funeral effigy is one of the few survivals of the Great Fire of London in 1666.

1666: The Great Fire of London destroys Old St Paul’s Cathedral

In the early hours of the morning of Sunday 2nd September 1666, a fire broke out in a baker’s shop in Pudding Lane, in the part of London commonly known as the City of London – an area contained within the old medieval walls.

It is thought that a stray spark from baker Thomas Farynor’s (Farriner) oven may have floated through the air to a nearby stack of fuel, which ignited and quickly spread. The summer of 1666 had been especially hot and dry, and these conditions led to the rapid spread of the fire, along with nearby warehouses filled with rope, oil and timber – all highly flammable. There was also a strong easterly wind blowing, which fanned the flames through the City’s narrow streets, with tightly packed wooden buildings with thatched roofs.

There was not initially much concern, even though there was no fire brigade at the time. It was left to Londoners and local soldiers to try and fight the fire as best they could with buckets of water, pumps (called ‘water squirts’) and hooks to pull down burning buildings. When told about the fire in the early hours of the Sunday morning, Lord Mayor Sir Thomas Bludworth dismissed it as not severe enough to need further action, but by the time it was daylight his attitude changed and King Charles II was alerted.

It was still burning on Tuesday 4th September, and by this point it had reached the medieval Cathedral of Old St Paul’s. Surrounded by the open land of the churchyard, it was thought that the building would remain safe from the flames; so much so that nearby booksellers and stationers took their stock down to St Faith’s Chapel in the Crypt, and local City residents placed their furniture and belongings in the churchyard for safekeeping along with bolts of cloth from nearby drapery sellers.

At around 8pm, a piece of burning wood flew through the air on the fierce wind that was still blowing. It landed on the roof of the old Cathedral, which had been covered with wooden boards to patch up damaged lead work. Not only this, the Cathedral was also covered in wooden scaffolding as a result of restoration work being carried out by Sir Christopher Wren.

With so much flammable material, the flames quickly took hold and were soon burning so brightly that they lit the night sky. Writer and eye witness John Evelyn wrote, ‘the stones of [St] Paules flew like grenados [grenades]…’, that the lead roof melted and flowed like a stream down Ludgate Hill, and that the pavements glowed red with the heat of the inferno. By the night of Wednesday 5th September the wind dropped, and by Thursday 6th the fire had eased off enough that Londoners could properly see the damage. 87 churches were destroyed, along with the Royal Exchange, the Guildhall, 13,000 homes – and Old St Paul’s was a ruined shell.

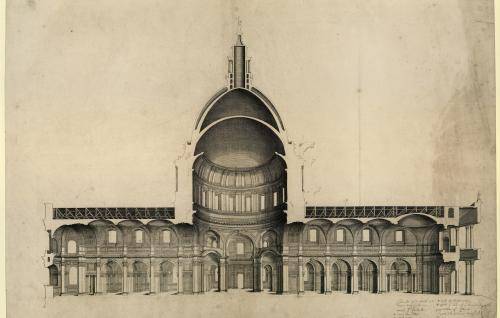

1668: Christopher Wren is appointed to rebuild St Paul's

Who would you choose to build a new cathedral for London? That was the question which faced the Church Commissioners and King Charles II after the Great Fire of London destroyed the cathedral which had stood in the City of London for over 500 years.

The task of designing and overseeing the construction of the new building required a huge range of skills and knowledge – a polymath who could manage people, finances and complicated engineering problems.

Christopher Wren (1632-1723) only took up architecture in his early thirties, with his first two commissions, both in Oxford, carried out in 1663. From his humble beginnings he could not have foreseen the extraordinary opportunities that would be afforded to him in the near future – as an architect to monarchs and as the designer of a new cathedral for London.

Before the end of 1661, Wren was unofficially involved in advising on the repair of Old St Paul's Cathedral. After two decades of neglect, it was in extremely poor condition – something which Wren put down to unfit building practices. He was therefore already connected to St Paul’s when, on September 3rd 1666, a fire began which would destroy much of the City of London and render the medieval cathedral structure unusable. When consulted, Wren had a clear vision of what was required:

‘The Cathedral is a pile for ornament and for use. It demands a choir, consistory, Chapter House, library and preaching auditory.’

All the spaces he listed were planned in to his Great Model design – his third proposal for a new cathedral. On 13th November 1673, on the basis of the Great Model design, Charles II appointed Wren architect to St Paul’s and the following day he received his knighthood. Until then his role had been advisory and with no official status.

The final design of the new St Paul’s was somewhat contested. The Great Model had been criticised for being not sufficiently “traditional” in its appearance, and Wren was not given the contract to begin construction until he created a design that was deemed appropriate. However, when building began, Wren’s Great Model design was clearly present; he had secured the King’s permission to make 'variations, rather ornamental than essential' which gave him license to follow his original vision.

1675: Henry Compton becomes Bishop of London

The last Bishop of London to ride into battle, Henry Compton was bishop during the rebuilding of St Paul’s after the Great Fire of London.

After a momentous life, he gifted nearly 2,000 books to help restart the Cathedral Library which had been lost in the fire.

Henry grew up in extremely turbulent times. England was in the grip of a civil war, in which his father was killed, and from which a complicated religious and political landscape emerged. He initially pursued a military career and rose to the rank of lieutenant, but in 1666 he turned to religion and joined the clergy, taking a number of positions in Oxford before becoming bishop there.

Henry was appointed as Bishop of London in 1675. HIs interests were international in scope: he was sympathetic to the struggles of Protestants across Europe who were experiencing persecution. He also engaged with the establishment of the Anglican Church in the American colonies and the founding of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel. In England, Henry became partly responsible for the education of Princesses Anne and Mary – the daughters of the future James II.

After James’ accession to become King James II, Henry openly opposed the policies of the King, particularly in relation to Catholicism, and as a result was removed from a number of positions. Henry later played a leading role in James’ removal, being one of the seven people who invited William of Orange to invade England and take the throne in 1688. He personally undertook the protection of Princess Anne when she deserted her father and fled Whitehall, riding alongside her carriage with a sword and pistols. With the arrival in England of William and Mary, Henry performed the Coronation ceremony, as the Archbishop of Canterbury was imprisoned at the time.

The book collection he donated to the Cathedral was an extraordinary gift – nearly 2,000 books from a major, up to date, scholarly collection. It included some significant Bibles, books on Christian ceremonies, general theological works, and several writers from both sides of the Reformation the 1500s. Many have neatly written annotations by Henry himself, showing how much he used them.

1711: New St Paul’s Cathedral is officially declared complete

On the 25th December 1711, Parliament declared the newly built St Paul’s Cathedral officially complete.

Construction had taken 35 years, which was a relatively short amount of time in cathedral-terms. Because of this it had been overseen by just one architect: Sir Christopher Wren, and had benefited from the skill, artistry and labour of countless others, from architect Nicholas Hawksmoor, sculptor Francis Bird, wood carver Grinling Gibbons and stonemasons Thomas and Edward Strong, to Jane Brewer – the only woman to feature on the list of craftspeople who had worked on the construction.

St Paul’s was consecrated in 1697 when the first service was held in the Quire, but at that point in time the Cathedral did not have its west end, or indeed the Dome. In the years between 1697 and 1708 the Dome would steadily rise, but without the promised spire, which Wren had added to his ‘Warrant Design’ – the design which had successfully secured his commission from King Charles II. Even without the spire though, the enormous size of the Dome would still dominate the London skyline; a remarkable feat of engineering supported with an inner cone made of bricks, and reinforced with iron chains at its base.

In October 1708, the Cathedral was topped out, and the last stone was laid on the lantern, which sits on top of the Dome. The ceremony was performed by Wren’s son Christopher, who had been born in the year that the construction began, and Edward Strong – the Master Mason – whose brother Thomas had laid the Cathedral’s foundation stone.

The remaining building works continued over the next few years until 1711 and even afterwards, but Sir Christopher’s final involvement with his beloved Cathedral was sadly overshadowed by conflict and difficulty. His plans for interior decoration, which included mosaics on the inner Dome, were not carried out, and pamphlets were printed suggesting that he had not been careful enough during the final years of construction, attacking his now ‘old fashioned’ taste. His salary was even withheld for a time.

Wren later retired to his house at Hampton Green near Hampton Court Palace, but from time to time would venture back into the city to visit St Paul’s, sit under the Dome and reflect on his work. After one such visit on the 25th February 1723, he fell ill and was found to have died in his sleep at the age of 91. He is buried in the Crypt of the Cathedral, where a simple stone marks his final resting place.

On the wall close by is a plaque added by Wren’s son Christopher with the now-famous Latin inscription, which in English translates to:

‘Reader, if you seek a monument, look about you.’

The first monument is placed on the Cathedral floor

The main floor of the Cathedral was left just as Christopher Wren had intended it for nearly 100 years following its completion.

The building offered long, clear views over the black and white tiles, between the cool classicism of its walls. The symmetry of the architecture was complemented by the carefully planned fall of light and shade.

In 1795, the architectural harmony of this vision was broken with the introduction of the first monument to the Cathedral floor – a statue to commemorate the well-known philanthropist and prison reformer John Howard. The decision to introduce the statue opened the floodgates to a deluge of monuments and memorials which, over the next century, began to fill the aisles, encrust the walls and even dominate the entrance to the Quire.

The arrival of the first monument owed its origins to a number of elements coming together at the same time. Notably, there was great public demand for a statue to commemorate John Howard. He was held in such high esteem that even before he died, there were calls for a statue to commemorate him, despite him preferring not to have one.

Howard had experienced imprisonment first-hand when captured off the coast of France while on his way to Portugal following the 1755 Lisbon earthquake. He went on to dedicate his life to prison reform, traveling by his own estimate some 42,033 miles, criss-crossing Europe to study incarceration and lazarettos (quarantine stations) abroad. He was systematic in his collection and presentation of data, which made his work highly effective.

Howard’s monument – by John Bacon – is still in its original location in the south east corner beneath the Dome. The carved marble depicts him in classical Roman robes, crushing a set of manacles beneath his foot, while holding his plan for improving prisons and hospitals in his left hand. Almost 80 years after his death, the Howard Association was formed in London, aiming to create ‘the most efficient means of penal treatment and crime prevention’ and to promote ‘a reformatory and radically-preventive treatment of offenders’. Its work continues today.

The Quire mosaics by William Blake Richmond are completed

The interior decoration of St Paul’s was a hotly-debated topic even before building work was completed in 1711.

It is sometimes assumed that the simple ceiling décor of the Nave, showing Sir Christopher Wren’s architectural details in all their beauty, show his vision for the interior decoration of St Paul’s – that anything more complicated or colourful would be a distraction from the architectural lines of the building.

Yet there is evidence in Wren’s biography Parentalia (written by his son, also named Christopher) that Wren had considered mosaic work for the Cathedral, as he admired the mosaics at St Peter’s Basilica in Rome. However, after the Dome murals by Sir James Thornhill were completed between 1716-19, there was always the worry that anything more colourful would make St Paul’s seem like a Roman Catholic church rather than Anglican.

It was not until the 19th century that this mindset began to shift, with what became known as the Oxford Movement. Some clerics within the Church of England – originally those associated with Oxford University – wanted to recognise and emphasise the Church’s Catholic heritage. At St Paul’s this influence was compounded by Queen Victoria’s severe assessment of the Cathedral as ‘most dreary, dingy and undevotional.’

Discussions on how to respond to the criticism included leading artists and designers of the day: George Frederick Watts, Alfred Stevens, William Burges, Frederick Leighton and Edward Poynter. Changes began between the 1860s and 90s, with mosaics added to the Dome spandrels (the top part of an arch) and St Dunstan’s Chapel built. Artist William Blake Richmond had also been involved in these earlier discussions, but it would not be until the 1890s that he would begin work on the largest area of the Cathedral to be decorated with mosaics – the ceilings above the Quire and Apse.

Richmond was named after his artist father’s close friend William Blake, and after studying painting in both England and Italy, he became a successful portrait artist. Later in his career Richmond turned his attention to large scale work and designs for stained glass and mosaics, and for St Paul’s he was inspired by the techniques used by mosaic artists in Byzantine churches. In these churches, pieces of mosaic were applied directly to the surface they were decorating, which created a more three dimensional effect that caught the light and was eye-catching when viewed from the ground.

Richmond first experimented by creating six mosaics off-site. Two were made in his own garden in Hammersmith and the next four at the workshop of glassmakers James Powell & Sons of Whitefriars before being transported to the Cathedral. Not totally happy with the way these turned out, later mosaics were installed on-site using specially constructed scaffolding, and the original stone was cut back so that the decoration would not stick out beyond the original walls and ceilings.

Work on the mosaics began in 1891 and was completed in 1904. These vibrant, sparkling designs include the Creation and other Bible stories, Old Testament and historical figures, angels, the Crucifixion, the Risen Christ and many animals, birds and flowers.

1924: The Great Restoration

One of the most extraordinary, but little known, feats in the history of the Cathedral is The Great Restoration of the 1920s.

It followed years of growing concerns, after the Cathedral was served with a Dangerous Structures Notice amid fears that the Dome might collapse.

Although much admired, by the 1920s, a Cathedral Canon described Christopher Wren’s design as ‘a somewhat bold and hazardous experiment’. Ominous cracks had appeared in the stonework and masonry had popped off and shattered. Measurements of the movement of the building found that parts were leaning nearly 30cm to the south west.

The leading architectural and engineering experts of the time applied themselves to understand and overcome the many structural problems which had developed in the building. Meanwhile, Cathedral staff and clergy worked hard to keep St Paul’s open for worship and raise the large sums of money needed for the restoration work.

3,000 cubic metres of stone were replaced, the two southern piers were reinforced by pumping cement in to the rubble core and the lantern at the top of the Dome was reinforced. But despite these changes, the City of London served a Dangerous Structures Notice to the Dean and Chapter of the Cathedral on Christmas Eve 1924. The notice called for the eight piers supporting the Dome to be completely taken down. A priest at St Paul’s replied on behalf of the Chapter, to say that it was ‘physically impossible for this requirement to be carried out’.

In March 1925, a team of over 200 workmen began new work to save the Cathedral. Over 250 steel bars were inserted into the piers and cement was injected at high pressure around them. A steel chain was placed around the outer drum of the Dome, tightened and reinforced with concrete.

To ensure regular worship could continue, the Altar was moved to the Nave, and the Dome and east end of the Cathedral were screened off. The organ was dismantled and rebuilt in the North Nave Aisle, and the new arrangements could comfortably seat over 1,000 people for a service.

Worship continued in this fashion until 25th June 1930, when the Cathedral held a special service to celebrate the completion of the restoration work and its grand reopening. The service was attended by King George V and Queen Mary and featured a procession of the 220 workmen who had helped to save St Paul’s. Not only had the building been saved from potential collapse, but the super-strengthening of the structure would help to save St Paul’s again during the Blitz.

1940: St Paul’s survives the Blitz

The night of the 29th December 1940 was the 114th night of the Blitz – the sustained bombing of Great Britain and Northern Ireland by the Luftwaffe during the Second World War.

During the Blitz, over 40,000 civilians were killed, with London bombed for 57 consecutive nights and over a million buildings damaged or destroyed.

On that night, the Daily Mail’s chief photographer Herbert Mason was on the roof of the newspaper’s building Northcliffe House, just off Fleet Street. He waited for hours to spot the Dome of St Paul’s through the thick smoke from fires raging across the City, and then: ‘Suddenly, the shining cross, dome and towers stood out like a symbol in the inferno. The scene was unbelievable. In that moment or two I released my shutter.’

Modern day analysis of the photograph – titled St Paul’s Survives – has shown that it was in fact heavily retouched in the studio, but it nevertheless remains a powerful image. On the 31st December 1940 it was published on the front page of the Daily Mail with the caption, ‘War’s greatest picture.’ The Cathedral, rising defiantly from the destruction around it, captured the hearts and minds of the public and became an enduring symbol of hope and resilience – yet it did not escape the war unscathed.

On the same night that Herbert Mason took his now iconic photograph, 28 small explosive devices fell on and around the Cathedral, hitting the Dome, and destroying the nearby Chapter House. Two months before, a 500lb bomb went off in the Apse and Quire, damaging the High Altar. In April 1941 there was another direct hit, this time to the North Transept. Such was the force of the blast that the walls were blown out of alignment. Bomb damage to some of the Cathedral walls can still be seen today, and the lack of stained glass windows in parts of the building are also sadly due to wartime damage.

In September 1940, a bomb landed beside the south-west tower but did not explode. Over three days it was dug out by a team led by Lieutenant Robert Davies, who worked tirelessly to remove the bomb and transport it to Hackney Marshes for safe detonation. Lieutenant Davies and Lance Corporal ‘Sapper’ George Wylie were later awarded the highest military honour for their efforts – the George Cross.

The St Paul’s Watch were a group of volunteer firewatchers, first set up during the First World War and reformed in 1939 by Godfrey Allen, Surveyor of the Fabric. The Watch included many members of Cathedral staff as well as other volunteers (notably a young John Betjeman) and later conscripted Post Office workers. It was thanks to their courageous efforts in patrolling, and using water pumps and sandbags to put out fires, that St Paul’s did not fall victim to flames once again.

Members of the St Paul’s Watch went on to found the Friends of St Paul’s Cathedral in 1952, and to this day, relatives of those who served in the Watch still make up its numbers.

1980: Prince Charles marries Lady Diana Spencer

On Wednesday 29th July 1981, Charles, Prince of Wales and heir to the British throne, married Lady Diana Spencer at St Paul’s Cathedral.

At the time, the public viewed the occasion as a fairy tale wedding, and the ceremony was watched by a global television audience of 350 million.

The choice of the Cathedral as a royal wedding venue was quite an unusual one. Senior royalty usually chose Westminster Abbey because of its rich royal tradition, and the wedding of an heir to the throne had not taken place at St Paul’s for 480 years – that of Prince Arthur (older brother to King Henry VIII) to Catherine of Aragon in 1501.

Prince Charles and Lady Diana chose St Paul’s over Westminster because of its larger capacity and the fact that the route between the Cathedral, Clarence House and Buckingham Palace, was longer – giving the public a greater chance of seeing them along the way. There were 3,500 guests at the wedding including Her Late Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, HRH The Duke of Edinburgh and other members of the Royal Family, heads of state, and members of other royal families from around the world.

The ceremony was due to begin at 11am but Lady Diana was a little late, arriving at the Cathedral’s famous West steps at 11.20am where she was welcomed by the Dean and Chapter, the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Bishop of London. Jeremiah Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary (The Prince of Denmark’s March) played as the bride made her way down the aisle accompanied by her father, Earl Spencer. The ceremony was conducted by the Dean, Alan Webster and the Archbishop of Canterbury, Robert Runcie. The music was a spectacle in itself, with three choirs and three orchestras present – including the Philharmonia Orchestra. Cathedral organists Christopher Dearnley and John Scott played, and the choirs were conducted by Choirmaster Barry Rose.

After the wedding vows were spoken, the Prince and new Princess of Wales were declared husband and wife, and made their way back down the Nave to the West doors. They were greeted by excited crowds outside, waiting to witness their carriage ride to Buckingham Palace.

1997: The first female priest is appointed at St Paul’s

The Revd Lucy Winkett was the first clergywoman to be appointed at St Paul’s in 1997, three years after women were first ordained as priests in the Church of England.

John Moses - then Dean of St Paul’s and a keen supporter of women’s ordination - appointed Lucy first as the Cathedral’s Chaplain, and then in 2003 as the Canon Precentor, the head of liturgy and music at the Cathedral.

The appointment was controversial, as women’s ordination had been both fiercely advocated for and opposed. The idea of women priests in the Church of England had been discussed as early as the 1920s, and the first woman to become a priest in the worldwide Anglican Communion was Florence Lim Ti Oi in 1944 in Hong Kong. In 1975, the Church of England passed a motion stating it had 'no fundamental objections' to women’s ordination, but there was a 20 year battle ahead before the first women were finally ordained.

One of the landmarks of the campaign was a clandestine meeting in the basement of 2 Amen Court – the home of Cathedral Canon John Collins, who chaired the meeting – where it was decided to set up a national movement to campaign for the ordination of women. The group became known as the Movement for the Ordination of Women (MOW), and was instrumental in changing the church.

In 1997, feelings were still running high, and Lucy’s appointment faced fierce opposition within St Paul’s and the Diocese of London. She received hate mail and abuse from those opposed to women’s ordination, some priests refused to accept communion or serve at the altar with her, and she was heckled while preaching. The opposition to her, she has since said, was ‘very public, distressing and enduring’.

Nevertheless, she became a much-loved and valued member of the Cathedral community, as a preacher, pastor and liturgist. She organised some of the Cathedral’s highest profile services of national celebration and remembrance, including the memorial services for those killed in the terrorist attacks in London in 2005 and the tsunami in 2006, and the service of celebration for the Queen’s 80th birthday. She chaired the Cathedral’s Make Poverty History event with speakers Kofi Annan and Gordon Brown, then Secretary-General of the United Nations and Chancellor of the Exchequer, attended by 2,500 people. In 2010, Lucy left to become Rector of St James’s Piccadilly, where she serves still.

Since 1997, the Cathedral has never been without a female member of clergy on staff. In 2018, Sarah Mullally was installed in St Paul’s as the first female Bishop of London – one of the three most senior posts in the Church of England – alongside the Archbishops of Canterbury and York. In 2004 and 2014, services of celebration of the tenth and 20th anniversary of women’s ordination were held at the Cathedral.

2020: St Paul’s closes its doors due to COVID-19

In early 2020, it became worryingly clear that the fast spread of the newly reported Coronavirus (or COVID-19 as it would become known) would have a serious and deadly impact on the world.

On the 19th March 2020, the Dean and Chapter of St Paul’s took the difficult decision to close the Cathedral doors – not just for sightseeing visitors but for prayer and worship, too. This was to protect public safety, and that of the Cathedral’s own staff and volunteers. Just a few days later on the 23rd March, the Government announced the first national lockdown.

At the time, it was difficult to imagine the ways in which the pandemic would change everyone’s lives, both day to day and through illness and bereavement. At St Paul’s, those staff who could do so began to work from home, and creative colleagues came up with ways to engage with the public digitally through online services, talks and resources for families, filmed prayers and reflections and virtual school visits. On-site clergy and staff worked hard behind the scenes to keep the building safe and clean, and to continue the daily pattern of worship and prayer even though doors were closed.

On the 22nd May 2020, St Paul’s launched the Remember Me project; an online book of remembrance for all those living in the UK who have died as a result of COVID-19. People of all faiths and none can contribute to the book, and it will remain open for as long as it is needed. Our former Dean, the Very Revd Dr David Ison said: ‘For centuries, St Paul's Cathedral has been a place to remember the personal and national impact of great tragedies, from the losses of war to the devastation of the Grenfell Tower fire. We have heard so many sad stories of those affected by the pandemic, and all our thoughts and prayers are with them. Every person is valued and worthy of remembrance.’

The Remember Me memorial space at the North Transept was opened in July 2022, and has an inner portico entrance dedicated to the memory of those who have died as result of the COVID-19 pandemic, alongside the online book of remembrance on screens inside the Middlesex Chapel.

People entering the Cathedral by the new Equal Access ramp at the North Transept go through the memorial into a tranquil space, and are able to take time to remember the many people who have died as a result of the pandemic.

Book your tickets

We have a number of sightseeing tickets available, with discounts for children, students, seniors over 65, and families. By booking online, you can also reserve a guidebook and a place on one of our expert-led tours.