Advent: The Art of Anticipation

Advent: The Art of Anticipation

Siobhán Jolley reflects on paintings in the National Gallery which anticipate the coming of Christ this Advent.

Emily Dickinson once wrote that hope is the thing with feathers. As we begin our Advent reflections, I want to suggest that Fra Filippo Lippi might well agree. His Annunciation (c. 1450-3), painted for the Medici family places feathers at the core of his vision of the hope of incarnation and salvation.

The angel Gabriel has arrived to bring the news to Mary that she will become the theotokos, the God-bearer. His wings of peacock feathers dominate his half the composition, curving to fit the panel’s unusual over-door shape. They remain unfurled, evoking the immediacy and immanence of this emissary episode. Nearby, the Holy Spirit, represented as a dove, hovers before Mary’s belly. Its tiny wings, a visual echo of those of the angel, ripple with motion, drawing our eyes to the hand of God the Father, who initiates this miraculous encounter.

Lippi situates this scene not in first century Nazareth, but within the Medici Palazzo, recognisable by the feathered family emblem visible on the low wall at the centre. Embedding the incarnation in his audience’s familiar world, his message is clear: hope is not distant or abstract but alive and present among us. The feathers, tangible yet weightless, remind us that God’s promise takes flight in the here and now.

The tension between the gentle fragility of feathers and their collective strength to allow wing-bearers to take flight, is an apposite metaphor indeed for the power of hope. As we reflect on this work and begin our advent journey in these uncertain times, let us be active in seeking out that anticipatory hope in our own contexts. Like Dickinson’s metaphorical bird and Lippi’s dove, hope may be fragile, but it is resilient, always poised to take flight.

In an age where we are bombarded with fleeting images, endless notifications, and relentless consumption, Sassoferrato’s The Virgin in Prayer offers a profound counterpoint to our chaos: a moment of stillness, focus, and peace. The painting’s understated simplicity is both striking and deeply affective. Through his baroque mastery of light, colour, and scale, Sassoferrato draws us into an intimate moment of transcendence, inviting us to witness—but not disturb—a sacred encounter.

Mary’s youthful features, gently clasped hands, and serene expression evoke a quiet surrender to the mystery of that first Christmas. She does not engage us, her eyes softly closed. This absence of gaze offers a gentle provocation that we too might need to avert our eyes from distraction. The beauty of the scene lies not in what Mary sees but in her quiet trust in what cannot yet be seen.

As screens dominate and bad news seems to flow endlessly, our eyes today are relentlessly occupied, searching for reassurance in what we can see, measure, and control. The Virgin in Prayer encourages us in a different direction. True peace, it suggests, is not external or visible. Mary’s closed eyes offer a quiet invitation to relinquish our saturated surroundings and to dwell instead in stillness and faith.

This call to trust beyond what is visible resonates especially in Advent, a season of waiting and preparation. Advent invites us to find peace not in what has already arrived but in what is yet to come. Sassoferrato’s Mary embodies this spirit of anticipation. The unseen peace portrayed here is not passive but profound—a quiet confidence in promises not yet fulfilled. Peace, it reminds us, is not a matter of what meets the eye but of what lies beyond it—a reality deeply felt even when it cannot be seen.

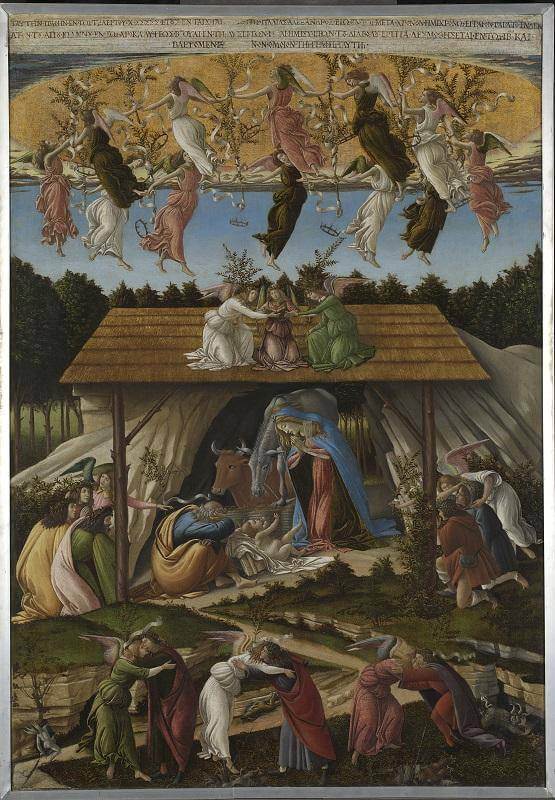

Botticelli’s Mystic Nativity is a kaleidoscopic delight of Advent themes: anticipation, joy, and divine mystery. Painted in 1500, it transforms the nativity scene from a private moment in history into a cosmic drama of hope and redemption.

All of creation is drawn into the joy of celebration, centred around the quiet joy of a mother with the child she has waited for. Surrounding the Holy Family, angels and shepherds join in celebration, their golden garments symbolising divine light illuminating human lives. Even as this joy transforms the world it transcends it, pointing towards eternal reconciliation. Mary’s quiet adoration of the Christ child anchors this eruption of transcendent joy in the radical simplicity of Advent: the joy of the divine breaking into the mundane.

Yet Botticelli also weaves a note of urgency into this tapestry of delights. The painting’s edges are alive with the chaos of a battle between angels and demons, evoking the spiritual tension that underpins Advent season. This imagery reflects the spiritual tension of Advent—a season of preparation where joy coexists with vigilance. This struggle reminds viewers that Christ’s coming is not only a moment of peace but also a call to recognise and resist the forces that oppose divine love. Yet, the radiant angels dancing serve as a vision of unity and reconciliation, affirming that happiness will overwhelm sorrow.

Through its transcendent joy and triumphant hope, Mystic Nativity reminds us that Advent is about more than waiting; it is a celebration of the promise fulfilled in Christ’s birth - the assurance that joy, not despair, will have the final word. Botticelli’s masterpiece is thus a visual meditation on Christian hope: Christ has come, Christ is coming, and the joy of his kingdom is already breaking into the world.

In the fourth week of Advent, Christians are invited to remember the love which underpins this season. The complexity of this love—beautiful and costly—is captured in Federico Barocci’s Madonna del Gatto (c. 1575). This intimate scene depicts Mary with the young Jesus and John the Baptist. The boys play with a goldfinch, observed by a playful cat who is ready to pounce. Painted for a private home, Barocci’s soft palette bathes the scene in familial warmth, drawing viewers into a moment of domestic tranquillity.

There is an overwhelming sweetness to the scene: Mary’s soft embrace, the innocent curiosity of Jesus, and the relaxed trust amongst them all. Barocci’s meticulous attention to detail—from the curls of the boys’ hair to the fine feathers of the goldfinch—deepens this tenderness. Yet, this kinship renders a more sombre truth all the more devastating. The goldfinch, a traditional symbol of Christ’s Passion, alludes to the blood he will shed. The cat evokes the rampant lion of the patron’s family crest, playing with ideas of power and vulnerability. These subtle details remind us that the joy of this moment is inseparable from the sorrow to come. Mary’s love is the love of a mother whose son has been born to die.

This is the deeper truth of the love we anticipate during Advent: it is a love that saves, but a love that costs. Barocci’s work reminds us that Christmas celebrates God’s extraordinary love entering into the mundane everyday. This love is not shallow or fleeting but enduring, costly, and redemptive. It is the love of God made known to us in a child, born in a manger to bear the sins of the world. This is the love we await this Advent and the love we are called to embody.

Dr Siobhán Jolley is a specialist in European Christian Art. She is Lecturer in Christian Studies at the University of Manchester and Visiting Lecturer in Christianity and the Arts at King’s College, London.