Painting the Passion

Painting the Passion

Ayla Lepine reflects on paintings in the National Gallery which illuminate our Lent, Holy Week and Easter pilgrimage.

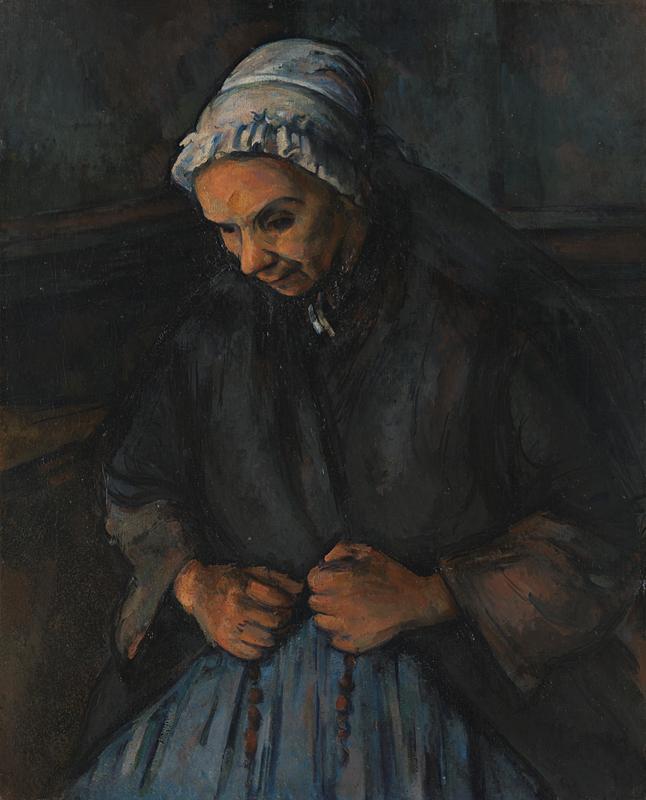

1. Cézanne’s Old Woman with a Rosary

Paul Cézanne, An Old Woman with a Rosary, c.1895-96 (National Gallery)

In 1896, the writer Joachim Gasquet found a painting on the floor of Cézanne’s studio underneath a leaky pipe. The water damage can still be seen on the painting today, and when I visit this painting in the National Gallery, that watery lower left corner of the picture makes my heart ache with empathy as though the painting itself has wept.

The woman in blue and grey with a halo-like white bonnet is vulnerable yet strong. She worked for Cézanne. She had been a nun, but by the time she and the painter met, she had left and was feeling lost. I’m drawn to her gentle patience. What have this woman’s dark eyes seen? She’s not aware of us, but she is aware of God’s presence. The Rosary beads she holds are a continuous circle of life with their prayer, ‘blessed art thou among women’.

This painting is not just visual, but tactile too. Her hands feel the round comforting beads slowly, one by one, and her pace slows me down too. My breathing becomes deeper, grounded in the rhythm of the prayer beads: the Lord’s Prayer, the meditations on Christ’s life, and that vital Rosary request: ‘pray for us now and at the hour of our death’. Lent is a time of study and prayer. I study art prayerfully each day. Colours, shapes, textures, and emotions lead us into new spiritual territory.

I’m part of an international group of priests called the Sodality of Mary. Our community’s prayer begins, ‘Father, in your love for us you chose Mary to be the Mother of your Son, the first to welcome him into her heart’. On Friday 25 March the Church celebrated the Annunciation. As we make our journey towards the cross in Lent, our prayers are shaped by the Passion of Mary’s Son, conceived in her sacred womb. Cézanne’s painting is an image of a strong woman’s trust in God, and I pray that we may deepen our trust together this Lent too.

Paul Cézanne’s An Old Woman with a Rosary is on display in Room 44 of the National Gallery.

A couple stand in their home, their hands touching. Arnolfini offers a greeting but doesn’t meet our eye. They are surrounded by delicate and curious objects. There are oranges – a sign of wealth, because they were so expensive – a candle, two dirty shoes, a fluffy dog, and a convex mirror. We catch a glimpse of a cherry tree’s glistening fruit. Though it’s spring, the couple are dressed in their winter best to show off their wealth.

The Arnolfini portrait is one of the world’s most famous paintings, and its serene mystery attracts millions. Despite all the detail, the crisp colour, and the intimacy of the couple’s shared space, they give little away. The mirror between them is surrounded by ten tiny scenes of the Passion of Christ. Its curved surface reflects two figures visiting the couple. The artist signed his name boldly: ‘Jan van Eyck has been here. 1434.’

This Passiontide I’m seeing this familiar scene with fresh eyes. A group of insightful young women visited the National Gallery with me last week and this was our first stop. They wondered about what kind of greeting the couple are offering, and the friendship represented by van Eyck’s bold signature and the possibility that he is one of the two people in the mirror. The painting, they said, is an uncanny threshold between public and private, sacred and secular, personal and impersonal.

The couple stand on holy ground, with Christ in the centre of their domestic life. Van Eyck’s own barely visible self-portrait is framed by Christ’s Passion. He took up his cross, by taking up his tiniest brushes. He gave all his skill to God, and this reminded me of the Eucharistic line ‘All things come from you, and of your own do we give you.’ The artist asks us to look deeply and slowly. He gives us the unexpected gift not of furs and oranges, but the image of Christ. That’s the real treasure here.

The Arnolfini Portrait is on display in Room 63 of the National Gallery

3. Michelangelo’s Entombment

Michelangelo, The Entombment (or Christ being carried to his Tomb), 1500-1 (National Gallery)

Michelangelo began The Entombment as an altarpiece for a chapel in Rome. The painting never made it to its destination, and remained unfinished. He abandoned it when Florence Cathedral gave him an offer he couldn’t refuse: a commission to sculpt David in marble. Michelangelo would be surprised, if not outright horrified, that this painting is one of the National Gallery’s treasures. Because it was never completed, it was never meant to be seen.

Christ’s body, strangely serene yet barely supported by the makeshift sling held by his friends, is depicted without wounds. Deposition scenes are usually horizontal, but this one is vertical, implying the possibility of the resurrection to come. Had it been installed as an altarpiece, the consecrated host, the Body of Christ, would have been raised by the priest in front of Christ’s luminous yet lifeless flesh. His face is tender and vulnerable, as the figures around him use all their strength to move his graceful body towards the tomb, which is barely visible between their feet. The figures’ hands, arrayed in a row across the middle of the painting, suggest a solidarity. Their feet are poised for action.

The surface is full of gaps and voids: the arm of the woman on the left whose finger points towards Christ, the cloak for the man in the back, the two figures in the distance, and the large expanse on the lower right, where Michelangelo would have painted the Virgin Mary kneeling in sorrow. Perhaps we can claim these strange unfinished spaces as places of prayerful waiting as we cross the holy terrain from Good Friday to Easter Day. In the Gospel of John, as Jesus is dying, he gasps, ‘It is finished’. Michelangelo’s unfinished painting draws us into the sacred expanse between the cruel violence of the crucifixion and the hope of resurrection.

Michelangelo’s The Entombment is on display in Room 61 of the National Gallery.

Swift and strong, three women dance to the rhythm of an unseen beat. Their vermillion boots swing out from beneath wide skirts of orange, green, blue and yellow. The same colours twist through their hair, ribbons flying in time with the music. These dancers travelled to Paris in the late 1890s, performing for audiences at the Moulin Rouge and the Folies-Bergère. Rural folk traditions enlivened Paris’ urban nightlife. But Degas doesn’t depict them on stage, as he did with countless images of ballerinas. The women appear to be in a field of fresh grass, a bright blue sky behind them. They embody the rhythms of nature’s renewal.

The flow of arms and sleeves, and the play of abstract shapes across the surface, create a visual rhythm. Degas invites us to share their joy. The pastel is thick, applied in exuberant layers. Bodies merge and twist as their movements become pure colour. They are a trio in harmony and every muscle expresses the new life of spring. They are Ukrainian. Today their blue and yellow ribbons proclaim a defiant joy. The feet that strike the ground in time to the music remind us of feet that walk mile after mile, exhausted and blistered, longing for safety, braced for danger.

At Easter we celebrate the glory of Christ’s resurrection, illuminated and inspired by God’s infinite love for all creation. This love gives us hope. As the American author and social activist bell hooks wrote, ‘The moment we choose to love we begin to move towards freedom, to act in ways that liberate ourselves and others.’ This week is Holy Week for the Orthodox Church. We pray with them and long for peace. Easter will come, with its holy rhythms of love and hope. Light overcomes darkness.

Peonies, lilies, honeysuckle, a keen-eyed grasshopper and dangling caterpillars all flourish in this painting. The radiant flowers stand out against the dark background, holding our attention with their vibrancy. Even the holes in the undersides of the rough leaves, their edges tinged with brown, are alluring in their details, punctuated with tiny dew-drops.

The seventeenth-century Dutch painter Rachel Ruysch ushered in an exciting new approach to still life, combining luxuriously precious blooms into arrangements that drew on her exceptional botanical expertise. The result was a composition in which Autumn and Spring blossoms cluster together in the same simple glass vase, their fresh stems intermingling in the clear water.

Our earth’s beauty season by season – so marred and endangered by today’s climate injustice – is reflected in the microcosm of this small canvas. The philosopher Elaine Scarry believes that when we see beauty, it inspires a deep desire to preserve, enjoy, and share it. Focusing on the wonder of nature can motivate us to protect it.

In the Easter work of Christ’s resurrection, every element of creation – every cell, every molecule – has been transformed by the infinite love of God. That work is beautiful. The medieval mystic Hugh of St Victor wrote, ‘By contemplating the works of God, we learn what ours should be. All nature speaks of God, all nature teaches humanity.’

When Jesus appears to the disciples and offers them peace, he gives each one of them what they needed in order to connect with the infinitude of God’s salvific love. The individuality of each flower in Ruysch’s vase, with its curling petals, hefty pistil, and delicate colours, form a kind of community, dwelling in unity. Though we know that flowers fade and the cycles of life and death continue, we trust the greater truth of eternal life that God has given us through Christ’s own divine beauty.

The Revd Dr Ayla Lepine is the Howard and Roberta Ahmanson Fellow in Art and Religion at the National Gallery, London and Assistant Priest at St Martin’s, Gospel Oak in North London.