Robert Faulknor

Image courtesy of Pantheons – Sculpture at St Paul's Cathedral (c.1796–1916) (york.ac.uk)

Robert Faulknor

1763-95

Part of War and resistance in the Caribbean: The monuments at St Paul's: A digital trail produced in collaboration with SV2G.

Note: We are only at the start of the journey toward centring the Caribbean voice in the Revolutionary Wars. The campaigns have traditionally been documented without a focus on the impact on local populations. Although the archival records offer limited information and this area of historical study is under-developed, our project raises awareness about the activities of the British campaigns in the Caribbean and their lasting legacies, and introduces visitors to a number of Caribbean heroes.

A significant military campaign during the French Revolutionary Wars was the British invasion of Martinique, Saint Lucia, and Guadeloupe in 1794, three French possessions of immense value to Europeans owing to the productivity of plantations worked by enslaved labourers. Faulknor first distinguished himself as a naval commander in March of 1794 when he led his men in the storming of Fort Royal, Martinique under heavy fire from French artillery. The British quickly captured Martinique, followed by Saint Lucia and then Guadeloupe in April of 1794. Guadeloupe was placed under the governorship of Thomas Dundas, though it was quickly recaptured again by the French commissioner Victor Hugues when he gained a huge boost to his liberating forces after proclaiming the abolition of slavery on the island. With Guadeloupe back in French hands, Captain Robert Faulknor was sent to Pointe-à-Pitre on the coast of Guadeloupe to capture a large French vessel (‘La Pique’) and stave off further French aggression. In the battle, Faulknor was wounded but continued to direct action until a second musket shot struck his heart and killed him, though shortly thereafter the French ship surrendered to the British.

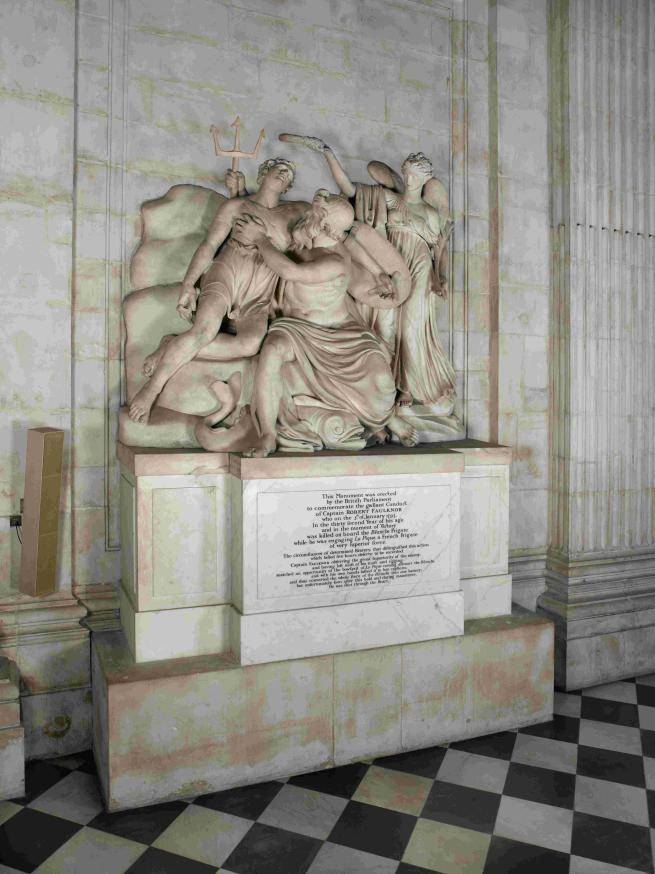

The British public were captivated by what they saw as a heroic death: the call to erect a monument at St Paul’s made by individuals who had resisted abolition efforts and supported slavery, including Admiral John Jervis (Earl St Vincent) and Lady Vincent, the Lord Mayor Sir William Curtis, City bankers Thomas Coutts and Robert Drummond, and slave traders Thomas King and Anthony Calvert. The monument shows the stricken Faulknor falling into the arms of Neptune, his right hand still holding the broken sword, and shield still strapped to his left arm. The figure of Victory, holding a palm, places a wreath of laurel on his head. At the base lies the mahi mahi, a tropical fish dwelling in the Caribbean characterised by its serrated teeth and a high flat forehead.

It is ironic that the only visual depiction on this trail which directly relates to the Caribbean is of a fish rather than a person. Though the people of Guadeloupe are invisible in this monument, the impact of the European struggle for domination over Guadeloupe was anything but invisible. In the space of ten years, Guadeloupe’s population experienced an invasion by the British, a war against the British, the abolition of slavery, the recapture of Guadeloupe by the French, and the reinstatement of chattel slavery.

On 7 June 1794, Victor Hugues, a commissioner sent from Paris, proclaimed the abolition of chattel slavery in Guadeloupe: it was an ideological attack against the British, who were opposed to revolutionary principles and the emancipation of slaves. The support Hugues gained from enslaved people and free people of colour enabled him to amass a large army and recapture Guadeloupe from the British. Though it is Faulknor’s bravery that is celebrated in this monument, the recently emancipated people fighting against him also showed incredible courage, both the men on the front lines as well as the women who looked after the injured during the British bombing of Pointe-à-Pitre.

The story of the people of Guadeloupe, so invisible in this monument, also continues beyond Faulknor’s life, not least in the figures of Louis Delgrès and the so-called ‘Mulatto Solitude’. These two individuals have come to symbolise determination, resistance, and self-sacrifice.

One of those fighting for the French alongside Hugues was Captain Louis Delgrès, a free, mixed-race soldier, who was taken as a prisoner of war to Portchester Castle in England. Upon his release, he travelled to France. But in 1802, just eight years after Hugues had proclaimed the abolition of slavery in Guadeloupe, Napoleon Bonaparte re-established slavery on the French Caribbean islands. Delgrès returned to Guadeloupe to take up arms again, this time against France, launching an initially successful campaign. But eventually he together with around 400 followers were surrounded at Matouba. On 10 May 1802, Delgrès issued a proclamation entitled ‘To the whole universe, the last cry of innocence and despair’. Eighteen days later on 28 May 1802, with French forces closing in and realising there was no escape, Delgrès and his followers lit the gunpowder stores, choosing to die by blowing themselves up rather than be captured and enslaved. Some were taken alive from the rubble and executed.

At this time, a young, mixed-race pregnant woman of around 22 years of age named Solitude joined the fight against the French. The only recorded mention of Solitude comes from Auguste Lacour’s 1855 book Histoire de la Guadeloupe. Calling her ‘The Mulatto Solitude’, he describes how she refused to abandon the rebel cause and was arrested with the insurgents and taken prisoner. She was sentenced to torture and death, and on 29 November 1802, one day after giving birth, she was hanged. Solitude is symbol of unknown women that fought for freedom and equality in the Caribbean. Several monuments in Guadeloupe today exist in her honour, streets and institutions bear her name, and many plays and works of art have been created to honour her memory.

There is also a memorial to Delgrès in Guadeloupe and an inscription honouring him in the Panthéon in Paris, where distinguished French citizens are buried and commemorated.

A key figure in the 1802 uprising, Solitude fought for freedom during a tumultuous time. She is a symbol of unknown women that fought for freedom and equality in the Caribbean.

Image source: Public domain image of bronze sculpture ‘La Mulatresse 'Solitude'' by Didier Audrat, Paris, 2022.

Captain Louis Delgrès, a free, mixed-race soldier, who has become a symbol of the fight for freedom. He was taken as a prisoner of war to Portchester Castle in England.

Image source: Public domain image of bronze sculpture ‘Commander Louis Delgrès’ by Didier Audrat, made in 32 copies and installed in each municipality of Guadeloupe, St Marteen and St Barthelemy, 2022.

Listen to an audio-recording of this text read by a member of SV2G. Sound recording by Marlon Lewis, Life in Frames.

For detailed information about this monument, visit the Pantheons: Sculpture at St Paul's Cathedral website.

War and resistance in the Caribbean

The monuments at St Paul's

Explore the full digital trail produced in collaboration with SV2G.