John Jervis

Image courtesy of Pantheons – Sculpture at St Paul's Cathedral (c.1796–1916) (york.ac.uk)

John Jervis

Earl of St Vincent (1735-1823)

Part of War and resistance in the Caribbean: The monuments at St Paul's: A digital trail produced in collaboration with SV2G.

The following entry has been researched and written in collaboration with members of SV2G.

Note: We are only at the start of the journey toward centring the Caribbean voice in the Revolutionary Wars. The campaigns have traditionally been documented without a focus on the impact on local populations. Although the archival records offer limited information and this area of historical study is under-developed, our project raises awareness about the activities of the British campaigns in the Caribbean and their lasting legacies, and introduces visitors to a number of Caribbean heroes.

Saint-Domingue, modern-day Haiti, was the most prosperous of all of France’s colonies and the site of one of the most important slave revolts. In August 1791, the enslaved population rebelled against French colonial rule. In desperation, white slave-owning French planters appealed to the British government for support in winning back the island and re-establishing slavery; in exchange they promised to submit to their authority. John Jervis and Ralph Abercromby were officers sent to the Caribbean initially to suppress the revolt, and then to conquer Saint-Domingue outright for the British. But the British army’s attempt to quell the revolt under the leadership of Toussaint Louverture and Jean-Jacques Dessalines, reconquer the land, and re-enslave the population failed, and they eventually withdrew from the island. In 1804, the island was declared independent under the Arawak-derived name of Haiti (Ayiti). The first independent Caribbean island was forced to pay reparations to France for their plantation owners from 1825, which in today’s money is valued at tens of billions of pounds.

Following the British forces’ failure to take Haiti, their invasion of Martinique, Saint Lucia, and Guadeloupe in 1794, three French possessions of immense value owing to the productivity of plantations, was highly celebrated. The campaigns were led by Admiral Sir John Jervis, who commanded the British fleet in the Caribbean, and General Sir Charles Grey (later the 1st Earl Grey), who led the British ground forces. Lessons were deployed from previous military campaigns to strengthen amphibious assaults (attacks carried out by troops that are landed by naval ships): the close cooperation between the army and navy which developed during these campaigns against the French became the foundations of British maritime supremacy. The difficult conditions faced by British soldiers under General Sir Charles Grey were presented to the House of Commons, including troops dying due to lack of medicines, the hospital in Martinique being overcrowded, and the sick being thrown by the seashore to die. John Jervis became celebrated for the reforms he made to the Royal Navy, including the use of fumigating lamps to protect his men’s health, and lightning conductors for his fleet. The landings involved a combination of regular British troops, local militia, and enslaved peoples whose freedom had been bought by the British in exchange for military service. Through the use of shock tactics (marching at night and storming positions with bayonets), Jervis and Grey achieved nearly all their strategic objectives in a single campaign. The British first secured Martinique, France’s most important Caribbean naval base, which capitulated on the 28 March. Guadeloupe represented another key target for British imperial ambitions, from which it hoped to secure colonial possessions and weaken French control in the Caribbean. The French general surrendered, and Guadeloupe was placed under the governorship of Thomas Dundas.

John Jervis was also assigned to lead the capture of Saint Lucia. In 1791, several commissaries were sent by France’s National Assembly to Saint Lucia to spread revolutionary ideas. Some of the enslaved ceased working and abandoned their estates, some white people of lower status (for example, those working for plantation owners) and free people of colour began to arm themselves, and the French Governor of the island fled. Faced with this breakdown of law and order and impending financial ruin, white plantation owners sought help from their rivals, the British. The British invaded Saint Lucia in April of 1794, led by John Jervis. But Victor Hugues, buoyed by his success in re-taking Guadeloupe from Britain, raised an army to resist the British. Following a series of bloody battles, the British were defeated and fled from the island, along with many of the planters. But the British continued to harbour hopes of recapturing Saint Lucia, and in April 1796, Ralph Abercromby again commanded a large flotilla to invade the island. On 26 May 1796, the French garrison holding Fort Charlotte on Saint Lucia surrendered to British forces commanded by Sir John Moore. Following this, the British went onto St Vincent in June 1796.

Jervis later became a household name following the famous 1797 victory against the French at Cape Saint Vincent in Portugal.

Jervis opposed the Slave Trade Abolition Act in the House of Lords in 1807, suggesting, according to the Hansard report, that ‘the West-India islands formed Paradise itself, to the negroes, in comparison with their native country’. The Hansard records also suggest that Jervis considered the bill a poor piece of legislation that would cause Britain to lose capital compared to other countries still involved in the slave trade, and that other nations treated enslaved peoples worse than the British did, which would defeat the humanitarian aims of the bill itself.

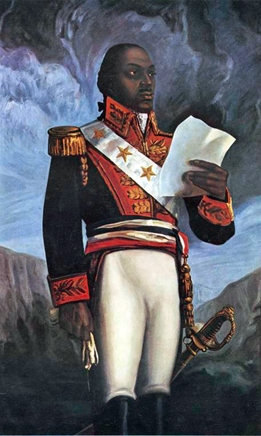

Depiction of General Toussaint Louverture, a self-educated former slave who played a crucial role in the Haitian Revolution.

Image source: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. 'Général Toussaint Louverture (1743 - 1803)' The New York Public Library Digital Collections, 1957.

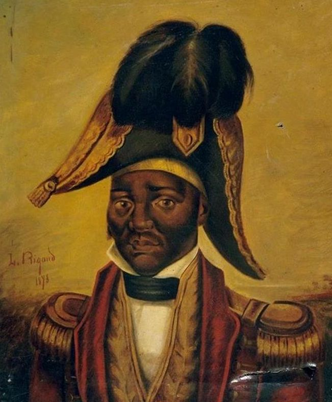

Portrait of Jean-Jacques Dessalines, who led a successful uprising against the British and became the first ruler of an independent Haiti, painted by Haitian artist Louis Rigaud in 1878. Image source: Public domain, courtesy of the Peabody Museum of Natural History, Division of Anthropology, Yale University.

Listen to an audio-recording of this text read by a member of SV2G. Sound recording by Marlon Lewis, Life in Frames.

For detailed information about this monument, visit the Pantheons: Sculpture at St Paul's Cathedral website.

War and resistance in the Caribbean

The monuments at St Paul's

Explore the full digital trail produced in collaboration with SV2G.