Sir Ralph Abercromby of Tullibody

Image courtesy of Pantheons – Sculpture at St Paul's Cathedral (c.1796–1916) (york.ac.uk)

Sir Ralph Abercromby of Tullibody

1734-1801

Part of War and resistance in the Caribbean: The monuments at St Paul's: A digital trail produced in collaboration with SV2G.

The following entry has been researched and written in collaboration with members of SV2G.

Note: We are only at the start of the journey toward centring the Caribbean voice in the Revolutionary Wars. The campaigns have traditionally been documented without a focus on the impact on local populations. Although the archival records offer limited information and this area of historical study is under-developed, our project raises awareness about the activities of the British campaigns in the Caribbean and their lasting legacies, and introduces visitors to a number of Caribbean heroes.

In 1796, Lieutenant General Sir Ralph Abercromby commanded a large flotilla to seize the island of Saint Lucia from the French. He then went swiftly onto Saint Vincent and the Grenadines (which the indigenous population called Yurumein) and Grenada where rebellions against the British were under way. Control over much of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines had been lost to rebelling French planters and native Caribs since early 1795, while Grenada was in the midst of an insurrection led by Julien Fedon.

Julien Fedon was a wealthy, free mixed-race person, born to a free mother of colour and a white planter father who had settled on the island after it was ceded to Britain in 1763. Inspired by the revolutionary ideals emanating from France, and recognising that it was the massive population of enslaved people (around 30,000) who were producing the wealth of the island, Fedon proclaimed a vision of Grenada as a Black republic. The revolt began on 2 March 1795, backed by the French Republic who, desiring a British defeat, provided freedom fighters with training and arms as well as promotion as French army officers. Fedon, who himself owned a large plantation estate called Belvidere, promised emancipation to the enslaved, and some 7,000 joined his forces in one of the largest slave rebellions in the Caribbean. As British subjects, Fedon and the other freedom fighters were committing treason against the British Crown. On 5 March 1795, just three days after the rebellion had begun, Governor Mackenzie issued a proclamation offering an amnesty to any individuals rebelling and promising to punish those who continued. The revolt continued and white British inhabitants were captured. When Fedon’s brother was killed in a skirmish, Fedon ordered the execution of 48 British prisoners, including the British governor of Grenada Ninian Home. The freedom fighters held most of the island for around a year, with the British having lost all their outposts save St George’s, the capital of Grenada, where the British forces were effectively trapped and soon beleaguered by yellow fever. But the British dispatched Abercromby to command an expeditionary force, and he landed in Grenada in 1796 with 5000 fresh troops. They captured Fort Matthew from the freedom fighters on 19 June 1796, dismantling a critical defensive position for the insurgents, and Abercromby ensured a blockade of key coastal areas to disrupt potential reinforcements or supplies for Fedon’s supporters. The uprising was suppressed, after which Abercromby implemented a series of repressive measures, including deportations and executions, to reassert British control and deter further revolts. Fedon’s fate remains unknown to this day: theories include that he jumped off a cliff, preferring death to capture, or that he escaped to Trinidad in a canoe. Statistics about casualties resulting from this conflict do not exist, but the British suppression of Caribbean islands did include shooting of the enslaved who were found carrying arms, deportation, and even hanging. At the conclusion of the war in January 1797, some of those who had participated in the rebellion returned to reclaim their forfeited property which included the loss of enslaved persons (legally considered chattel, or personal property). The British Crown set up Commissioners to preside over these cases, calculate their losses and provide compensation. This presented confusing and unstable experiences for those who were enslaved due to interchanging ownership, being sold or returning to their previous owners.

The uprising in Grenada directly influenced the revolt in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines in 1795, in which freedom fighters held the island for six months before, again, being conquered by Abercromby. Saint Vincent and the Grenadines had been inhabited by the indigenous Carib people (the Ciboney, Taino and Kalinago people) before European colonization, who later intermixed with the enslaved peoples of Africa now known as the Garifuna people (plural Garinagu). The island, which had been known by the name of Hairouna and Yurumein, changed hands multiple times between the French and the British during the eighteenth century, causing great tension between the indigenous people and the European powers. In the late 1700s the First Carib War was fought by the Garifuna people (Black Caribs) in response to British attempts to extend colonial settlements into their territories and establish control over the island. A 1773 peace agreement had restrictive terms, for example reducing the land rights of the Garinagu people and punishing them with further seizure of property if they did not help capture runaway enslaved people. Grievances and resentment continued and, supported by the French and revolutionary fervour, the Garifuna people rose again to resist the British. Garifuna Chief Joseph Chatoyer (Satuye), led over 1000 freedom fighters against British expeditionary forces during the Second Carib War. Employing military tactics unknown to the British, Chatoyer took advantage of the rugged terrain of the Leeward side of Saint Vincent to launch surprise attacks on British forces, crucially taking Dorsetshire Hill in 1795. Chatoyer was killed in a skirmish with the British on 14 March 1795, becoming a symbol of Carib resistance; the date is still annually observed as National Heroes Day in memory of the struggle against British and French colonialism. At the same time, his brother Du Vallée led the other side of the island in uprisings for another year. Abercromby was once again tasked with suppressing the Carib resistance and maintaining British control over Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and his expedition defeated the Garifuna people in October 1796. Local island militia such as the Black Rangers, recruited by the British, were key to winning the war in Grenada and St Vincent and the Grenadines. Abercromby acknowledged that they had offered ‘essential services’. Some of the forces upon whom he relied, and who had been involved in the capture of the islands, included the 14th Regiment of Foot, which became the Buckinghamshire Regiment.

The impact of the British victory over the Carib population was so severe that it is considered by some to be one of the greatest acts of genocide committed by the British. Abercromby carried out orders for nearly 5,000 Garifuna people to be exiled to the uninhabited island of Baliceaux, where over half of them died before the survivors were transported to Roatán, off the coast of Honduras. Among the survivors that arrived in Roatán were two of Chatoyer ‘s children and his brother Du Vallée. The Garifuna people eventually settled in Honduras, Belize, Guatemala, and Nicaragua, managing against all odds to preserve their distinct cultural identity, traditions, and language in their new communities. In 2001, UNESCO proclaimed the Garifuna culture a ‘Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity’.

The St Vincent’s Black Corps Medal commemorates the suppression of a rebellion in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. One side of the medal depicts a winged figure of Victory with a sword over a fallen Garifuna person. The reverse features a soldier, possibly enslaved, holding a musket and a bayonet with the inscription 'BOLD LOYAL OBEDIENT'. Image source: medals.org.uk.

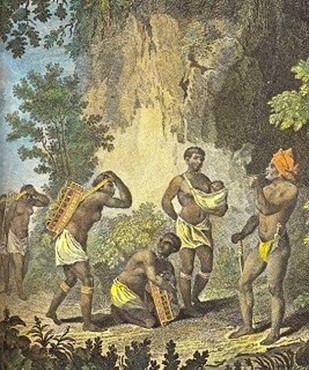

Image from print engraving, «‘Chatoyer the Chief of the Black Charaibes in St. Vincent with his five wives ' [graphic], Drawn from the life by Agostino Brunyas (Brunias) -- 1773, From an original painting in the possession of Sir William Young, Bart, F.R.S. ; Grignion sc. » (London: Stockdale, Piccadilly, 1801) Location: Library Company of Philadelphia Edwar 18058.O v 3 p 262.

Listen to an audio-recording of this text read by a member of SV2G. Sound recording by Marlon Lewis, Life in Frames.

For detailed information about this monument, visit the Pantheons: Sculpture at St Paul's Cathedral website.

War and resistance in the Caribbean

The monuments at St Paul's

Explore the full digital trail produced in collaboration with SV2G.