Thomas Dundas

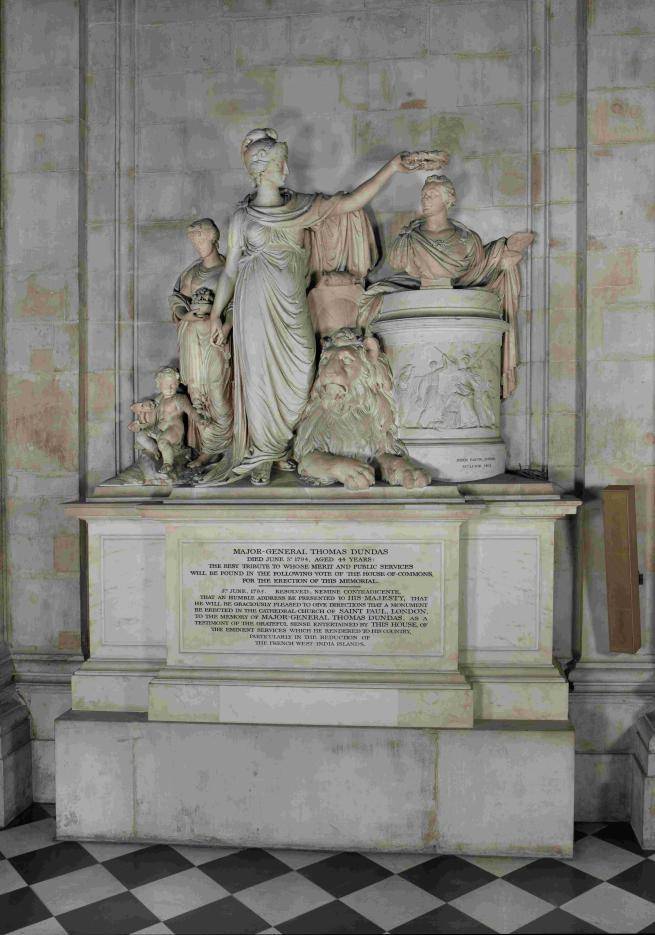

Image courtesy of Pantheons – Sculpture at St Paul's Cathedral (c.1796–1916) (york.ac.uk)

Thomas Dundas

1750-94

Part of War and resistance in the Caribbean: The monuments at St Paul's: A digital trail produced in collaboration with SV2G.

The following entry has been researched and written in collaboration with members of SV2G.

Note: We are only at the start of the journey toward centring the Caribbean voice in the Revolutionary Wars. The campaigns have traditionally been documented without a focus on the impact on local populations. Although the archival records offer limited information and this area of historical study is under-developed, our project raises awareness about the activities of the British campaigns in the Caribbean and their lasting legacies, and introduces visitors to a number of Caribbean heroes.

Major-General Thomas Dundas, later the Governor of Guadeloupe, served under the command of Admiral Sir John Jervis and General Sir Charles Grey, and played a leading role in the 1794 invasions of Martinique, Saint Lucia, and Guadeloupe, three French possessions of immense value owing to the productivity of the plantations. Guadeloupe represented a key target for British imperial ambitions, from which it hoped to secure colonial possessions and weaken French control in the Caribbean. The amphibious assault on Guadeloupe was led by Admiral Sir John Jervis, who commanded the British fleet in the Caribbean, and General Sir Charles Grey (later the 1st Earl Grey), who led the British ground forces. The landings involved a combination of regular British troops, local militia, and enslaved peoples whose freedom had been bought by the British in exchange for military service. The French general surrendered, and Guadeloupe was placed under the governorship of Thomas Dundas. However, shortly afterward, Dundas died of yellow fever, and his force was similarly decimated by the illness. Reinforcements failed to arrive to consolidate the British possession of the island, and the French commissioner Jean-Baptiste Victor Hugues quickly took advantage. Promoting revolutionary causes and prompted by a new French law which granted freedom to enslaved people, Hugues proclaimed the abolition of slavery in Guadeloupe in June 1794. In the space of a few months, he was able to rally crucial backing from the local population: while some continued to support the British, the vast majority of free inhabitants on the island, both white and people of colour, lent their support to the Republic, and he had the overwhelming support of emancipated enslaved Africans whom he incorporated into his army. The conflict resulted in hundreds of deaths on both sides, and large numbers of local royalists were executed. Hugues quickly recaptured Guadeloupe from the British.

Upon his victory, Hugues described the British seizure of the French islands as an unparalleled crime which violated the rights of humanity and nations. He had Dundas’ body exhumed and left for the birds, and a monument was prepared to record how Guadeloupe was ‘restored to liberty by the bravery of the Republicans’ after it ‘was polluted by the body of Thomas Dundas, Major-General and Governor of Guadeloupe, for the bloody George III’. This extreme act was consistent with Victor Hugues’ regime: though he is seen as a liberator of the enslaved and a successful exponent of racial integration, he is also simultaneously considered a radical whose methods were in keeping with the bloody radicalism of the Reign of Terror, including the use of a guillotine for executions. This was a period in France during which the Jacobins, a revolutionary political group, committed numerous public executions of those whom they accused of treason.

The humiliation of Dundas’ body provoked great outrage amongst the British public and prompted the call for a monument to be erected in his memory at St Paul’s. Praising Dundas for ‘the eminent services which he rendered to his country, particularly in the reduction of the French West-India Island’, the sculpture shows a semi-naked warrior representing ‘Anarchy’ attacking Britannia with a torch and swinging a severed head, reflecting the view held by many British people about the barbarism of the French Revolution.

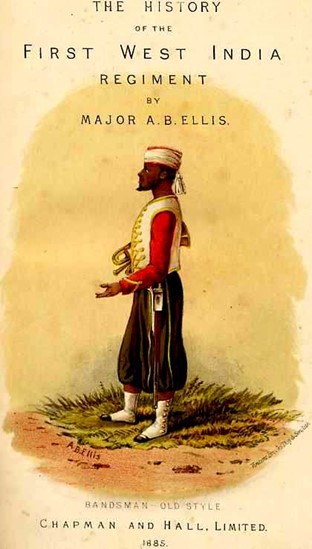

To fight the wars in the Caribbean, the British purchased enslaved peoples in exchange for military service. The uniform worn by the enslaved was known as the ‘Zouave’. Many of these soldiers served in infantry units that eventually became known as the West India Regiments. Although the regiment was disbanded in 1927, the Barbados Defence Force Band still wears this uniform today. Image source: Public domain, from Colonel A. B. Ellis, The History of the First West India Regiment (Chapman and Hall: 1885), p.iv.

Listen to an audio-recording of this text read by a member of SV2G. Sound recording by Marlon Lewis, Life in Frames.

For detailed information about this monument, visit the Pantheons: Sculpture at St Paul's Cathedral website.

War and resistance in the Caribbean

The monuments at St Paul's

Explore the full digital trail produced in collaboration with SV2G.