Thomas Picton

Image courtesy of Pantheons – Sculpture at St Paul's Cathedral (c.1796–1916) (york.ac.uk)

Thomas Picton

1758-1815

Part of War and resistance in the Caribbean: The monuments at St Paul's: A digital trail produced in collaboration with SV2G.

The following entry has been researched and written in collaboration with members of SV2G.

Note: We are only at the start of the journey toward centring the Caribbean voice in the Revolutionary Wars. The campaigns have traditionally been documented without a focus on the impact on local populations. Although the archival records offer limited information and this area of historical study is under-developed, our project raises awareness about the activities of the British campaigns in the Caribbean and their lasting legacies. and introduces visitors to a number of Caribbean heroes.

This is the only monument to a Welshman in St Paul’s Cathedral. It makes no allusion to Sir Thomas Picton’s role as Governor of Trinidad, a post he held from 1797 to 1803. Picton was one of the most controversial figures in the British army. When British fleets, under the command of Lieutenant General Sir Ralph Abercromby, seized Trinidad from the Spanish in 1797, Abercromby appointed Picton the Governor-General of Trinidad, a post he held from 1797 to 1803. His governance was characterised by cruel and oppressive methods: Picton maintained order through torture and dozens of executions designed to scare all the inhabitants – British soldiers, enslaved workers, free subjects, and potential opponents – into obedience, therefore he was commonly referred to as the ‘Tyrant of Trinidad’ by his contemporaries.

Picton later justified his violent policies by pointing out the importance of discipline in order to ensure Trinidad’s security as a strategic possession. French and Spanish enslavers, many displaced from other islands by slave revolts or by the French revolutionary government’s abolition of chattel slavery, had settled in Trinidad; they called on Picton to take a hard line against revolutionary ideas, uprisings, and disruptions to their trade. In 1797 Picton had an artilleryman executed without trial for purportedly raping and robbing a free woman of colour. He hanged a Spanish labourer for being drunk and disorderly. Picton also had a mixed-race Trinidadian man executed in front of his father-in-law for planning to smuggle three Guadeloupean activists onto the island to help organise an uprising against the British.

Picton introduced a new draconian Slave Code which stipulated extreme punishments, and he became a plantation investor himself, with investments culminating in a £50,000 deal for a large estate and 113 enslaved Africans. During his period as Governor the population of enslaved black workers in Trinidad almost doubled (to around 19,700 people), as did sugar exports. This put him at odds with the British colonial government, who at this time was considering plans to transform Trinidad from a chattel slave-based economy to a white settler colony as a way to solve Britain’s domestic issues, by deporting outcasts, former prostitutes, and Highland Scots to the island.

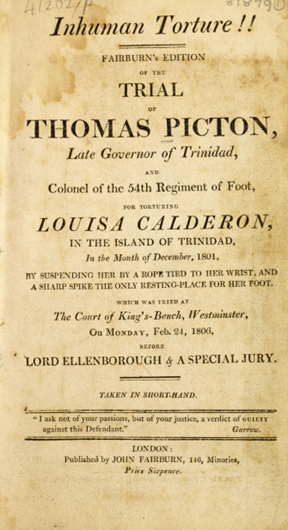

When William Fullarton was invited to jointly govern Trinidad with Picton, Picton resigned. Soon Fullarton brought charges against Picton for his acts of brutality. He faced trial for only one charge, that of permitting torture against a young free mixed-race girl of between 11-14 years of age, Louisa Calderon, accused of stealing money from a Port of Spain businessman, Pedro Ruiz. The method for obtaining a confession was ‘picketing’ (which an outraged British public would later describe as ‘Picton-ing’), suspending the individual from a pulley with foot held in place by a sharp piece of wood. Picton’s guilty verdict was overturned on appeal two years later, on the basis that torture was legal under Spanish law, which was still in force in Trinidad at the time. Other than legal costs, Picton never faced any punishment for his brutal methods.

The trial caused a sensation among the British public who were shocked by the graphic nature of the charges, having been largely ignorant about the realities of colonial violence. Picton was outraged by the perceived bias which portrayed Calderon as an innocent victim rather than, in his description, ‘a common Mulatto prostitute, of the vilest class and most corrupt morals’ who had formed criminal connections and been a thief. But Calderon, herself highly articulate and giving testimony at the trial as a now-sixteen year old (and asked even to re-enact her torture), became a symbol in the eyes of the British public of the horrors of colonial rule. The British public were also entranced by Calderon’s position as a free mulatto girl. Lighter-skinned women received better treatment, but were more frequently the object of sexual exploitation, to secure position or commercial advantage. The coverage of Louisa’s case in the British media accentuated the eroticisation of mixed-race women. One frontispiece portrayed Calderon with her breasts exposed and dangling as her arm hangs from a scaffold; other prints portrayed a naked Calderon being leered over by a jailor.

Where Louisa Calderon was victimised, another woman was villainised: Rosetta Smith, the mixed-race mistress of Thomas Picton and the mother of his four children. The British press portrayed her as a power-hungry temptress who had seduced Picton into giving her free rein over the colony, and a co-conspirator of his corruption and crimes.

Picton’s reputation was redeemed in contemporary eyes by his heroic death as the highest-ranking officer killed at Waterloo, leading to a number of streets, buildings, and places being named after him in Britain and in the Caribbean, including Fort Picton in Trinidad and Tobago. In addition to the monument here, his body lies in the crypt of St Paul’s, near the tomb of the Duke of Wellington.

Listen to an audio-recording of this text read by a member of SV2G. Sound recording by Marlon Lewis, Life in Frames.

For detailed information about this monument, visit the Pantheons: Sculpture at St Paul's Cathedral website.

War and resistance in the Caribbean

The monuments at St Paul's

Explore the full digital trail produced in collaboration with SV2G.