Fair Money

Fair Money

Alan Smith considers issues of equality, fairness and justice in money and the economy.

1. To those who have, more shall be given?

The Parable of the Talents (Matthew 25, 14-30) is often used as a key example of the way in which Christianity and capitalism sit well together. It seems to encourage us to celebrate the two individuals who were given money at the outset and how they doubled it through their investment and trading skills. The character who “according to his ability” started with one talent, and buried it in the ground, usually gets opprobrium. In a further call out for the financial system, he is admonished that “you should have put my money on deposit with the bankers”.

Is this view right?

Perhaps the parable is not signalling the virtues we think it is. Some argue that Jesus is, in fact, throwing a spotlight on how the economy works in the real world in all of its ruthlessness and inequity. Those with more capital are typically at a distinct and unfair advantage.

Arguably, the person with the one talent was the one with integrity, the true hero. He spoke truth to power, saying “you are a hard man, harvesting where you have not sown and gathering where you have not scattered seed”. He refused to play the game unless fundamental truths about their economy were faced.

I am sympathetic to this view. And I believe that the Parable of the Talents also speaks to the ruthlessness and inequity of our 21st century economy which leaves those without capital very vulnerable. Leading economists like Thomas Piketty, Angus Deaton and Branko Milanovic write very powerfully today of the increased levels of inequality and its detrimental impacts on economy and society. The functioning of the economic system still feels as if it privatises the profits for the wealthy few, and socialises losses so that they are borne by many who are under resourced.

The powerful voices of economists must be complemented by the moral and theological voice of the Church. The voice of the invisible God needs to shape the invisible hand of the market. Like the person with the one talent, God’s Church must speak truth to power. This might come at great cost. Are we willing to pay it for a just and flourishing economy?

2. God Bless the Child in an AI Age

“Them that's got shall get

Them that's not shall lose

So the Bible said and it still is news”

So sang Billie Holiday in “God Bless the Child” when she released it almost 70 years ago. She continues:

“Yes, the strong get more

While the weak ones fade

Empty pockets don't ever make the grade”

Artificial Intelligence is at the centre of global conversations these days, and we need a call to action to prevent those lines in “God Bless the Child” from becoming the anthem for our AI age.

Artificial intelligence is a game changer transforming where we work, how we work, and the work we do. Computers can independently learn, think, solve problems, and perform a wide array of both simple and complex tasks commonly associated with intelligent human beings. They can undertake many professional tasks and even produce original works of art and compose music. AI will play a big part in determining “them that’s got, and then that’s not”, indeed in ascribing value to one human life relative to another.

Jobs will be destroyed but new jobs will be created. The World Economic Forum's (WEF) current (2023) projections are that 69 million new jobs will be created over the next five years driven by new technologies and the Green transition. The nature of jobs and skills in demand will of course be very different. 44% of workers' core skills are expected to change in the next five years.

The wealthy with their resources, their networks, and well-resourced private schools can invest effectively to make the most of the opportunities ahead. But the daily pressures of putting food on the table and a roof over one's head leave too many ordinary families without the bandwidth to invest in similar ways.

A woeful lack of public investment in the education, skills, and mindset/culture shift necessary for ordinary people to make the most of opportunities in an AI world has left our society with an unfair distribution of income-earning potential.

Our Churches must step in and step up. Churches are uniquely well-placed to speak truth to power and advocate on behalf of the voiceless and the powerless. We are also well equipped to work through our institutions and schools to deliver the education, upskilling, and mindset/culture shift necessary to flourish in an AI world.

God can indeed "bless the child" in an AI world through our Churches.

3. Is the Love of Money the Root of All Evil?

In a 1998 study, participants were asked how much salary they would prefer to earn in the following scenarios:

Scenario A: £50,000 whilst others earned £25,000; or

Scenario B: £100,000 whilst others earned £200,000.

Approximately 50% of the participants chose to earn the lower amount of £50,000. They loved earning more than others more than they loved money itself. And they clearly had no desire to be wealthier if more money came with lower status.

This is a fascinating insight into human behaviour which suggests that perhaps many who seem driven by money, are in fact primarily driven by the love of the status money can buy.

Is this why so many of us are very comfortable with growing inequality despite clear evidence of the damaging effects of inequality on us as individuals and society as a whole?

Apparently.

Income inequality has been rising for the last 60 years, with a rapid acceleration about 40 years ago. Our UK income inequality is now one of the highest among developed countries. And we have paid a very high price indeed.

Research shows that more unequal societies have less economic stability, less social mobility, and more property crime and violent crime. More unequal societies also breed more stress and more status anxiety with damaging effects on our physical and mental health. Vicky Spratt in last week’s Sunday Observer newspaper explored the extent to which growing inequality may be ruining friendships and family relationships.

But there are studies out there to suggest that this love of status and inequality isn’t necessarily encoded in our DNA. Several decades ago, an anthropologist proposed a game to a group of children in Kenya. He put a basket of fruit near a tree and told the kids that whoever got there first would win the fruits. The children all took each other’s hands and ran together, then sat together and enjoyed their treats together. When the stunned researcher asked why individual children did not try to win the race, they responded ‘UBUNTU’ which in the Xhosa culture means: “I am because we are”. How can one of us be happy if all the other ones are sad?

It is about time we end this love affair with status and inequality. It is about time we choose to live simply so that others could simply live.

4. Slavery, Capitalism and Climate

There are remarkable similarities between Transatlantic Chattel Slavery and the Climate Crisis. Transatlantic Chattel Slavery at its heart was tantamount to human sacrifice on an industrial scale in the ruthless quest for profit - millions of souls tortured, traumatized, and extinguished through violent commodification as energy sources on plantations in the Americas.

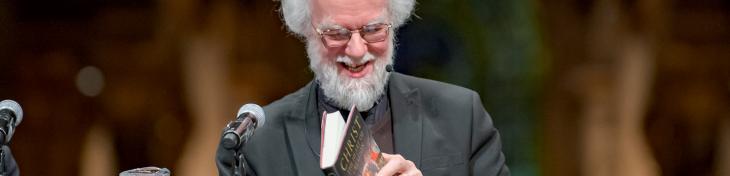

No wonder the Archbishop of Canterbury named this crime against humanity “one of the highest forms of blasphemy against God”. Theologically speaking, these acts of extreme violence against God’s image bearers in pursuit of money represent a declaration of war against God Himself.

So have we moved on? Hardly. We have despoiled and continue to despoil God’s beloved creation in the ruthless pursuit of other energy sources - and profit. The temperature rises due to climate change catalysed by the overexploitation of fossil fuels are placing hundreds of millions of souls – God’s image bearers – at risk.

We still seem all too comfortable with human sacrifice on an industrial scale in the ruthless pursuit of profit. We are still waging a war against God through desecrating and destroying His image bearers in the millions.

But how can we expect to continually wage war against the God who created the cosmos in pursuit of money and win? Isn’t it time we lay down arms?

…..

When the weight of moral argument and economics prompted vested interests to move away from chattel slavery, they behaved in ways that uncannily mirror oil companies and financial institutions of today.

They attacked the science.

We sometimes hear economics called “The Dismal Science”. The term was coined by Thomas Carlyle who attacked economists for daring to challenge slavery on both moral and economic grounds. He decried their arguments that the best way for human flourishing was “letting men alone”, letting all human beings have personal freedom, consistent with all of us being created in the Image of God.

Climate change denialists certainly seem to be the Thomas Carlyles of our day.

Vested interests took ostensibly benevolent actions that obscured the blood money which continued to flow unabated. Some call this “black washing”. Even as England congratulated itself on the abolition of the slave trade in 1807, the City of London pivoted towards financing the slave trade with the emerging markets of the day – in particular the USA and Brazil.

Also in 1807, vested interests produced “The Slave Bible” for “the use of the Negro Slaves in the British West Indian Islands”. This bible cut out about 90% of the Old Testament and 50% of the New Testament, leaving only passages that encouraged the slaves to be contented with their lot and continue to generate healthy profits.

Self-congratulatory celebrations on the abolition of slavery itself obscured the fact that vested interests actually grew richer still through compensation that both the slaves and the British taxpayer were forced to pay.

The slaves were forced to provide an extra four years of unpaid labour. The British taxpayer was forced to pay the slave owners £20 million - 40% of the national budget and the equivalent of £17 billion in today’s money. The loan taken to fund this compensation payment was only finally paid off by the British taxpayer in 2015.

So even as 21st-century corporates who profited from polluting our environments demand incentives (compensation?) for transitioning to a low-carbon economy, we have a sense of déjà vu.

And even as climate activists express concern about “greenwashing”, we are reminded of the “black washing” which took place when ostensibly benevolent acts obscured the extent to which vested interests continued to maximise profits from the crime against humanity which was slavery.

Slavery reminds us of the immoral choices that we make about money, just as climate change does today. Its history has many pointers as to how vested interests of today may well act. As we move towards COP28, we must seek a better way. We must seek God’s help and commit to breaking history’s cycle.