Art, faith and ordinary time

Art, faith and ordinary time

Deborah Lewer reflects on how great works of art might help us reflect on ourselves, our faith and the world around us.

1. Albrecht Dürer’s The Great Piece of Turf

In the church’s liturgical calendar, we are in ‘ordinary time’. So, this October, we’ll be looking each week on a work of visual art that gives form to the mundane, the everyday, the unremarked and the overlooked. In many ways, our times are anything but ordinary. But looking, with artists, at the generative potential of the ordinary in life and faith can re-ground us. More than that: it might open our eyes to unforeseen beauty, mystery, wonder and hope – in the very midst of everyday life. Albrecht Dürer was an ambitious, spectacularly gifted and prodigiously skilled artist.

Working in Germany and beyond on the eve of the Reformation, he recorded his own countenance in some of the history of art’s most astonishing and audacious self-portraits. He had a deep faith and conversed with the leading philosophers and theologians of his age. His unsurpassed prints circulated widely and influenced profoundly the leading artists of Renaissance Europe. And while all this was going on, he was out in the fields, on his knees, looking intently at soggy, muddy, clumps of earth and the messy tangle of common wild plants – those some call ‘weeds’.

Dürer’s Great Piece of Turf is a watercolour painting of the finest intricacy. We can see in it the artist’s skill as a craftsman, his heritage in Nuremberg’s tradition of goldsmithing. We can sense his close investigation of the complex ecology of this piece of earth, full of life. Every stem, leaf, seed head, root and clump of sod is rendered with exquisite attention. Set against a pure white void, all is heightened. And it’s not just about what grows above the surface – the very earth is opened to us here too. There’s a puddle at the base of his clump of turf. The water’s transparency makes visible the interconnectedness of the root system. It both sustains and reveals the source of all the life that has grown and all the new life to come. We see the seeds just forming, in the heads of the dandelions. We know the breath of air that will carry them to new life. In the history of art at that time, such high scrutiny of such lowly subject-matter was unprecedented. Yes, Northern European artists had long trained their eyes on nature and all details of the real. But making an ordinary tangle of plant matter without centre, without hierarchy, without symbolic portent the sole subject of such a highly finished work was a radical act. Of what?

What does it mean to lavish this degree of attention on something so ordinary? In her poem on Dürer’s piece of turf, the poet Rita Dove wonders: ‘What possessed him to tote it home?’ What indeed? The late, great writer on art, John Berger, once said that ‘painting collects the world and brings it home’. We could think about the other ways things immeasurable can come to us in the form of something as ordinary, as finite, as humble and as unique as a human being or as the very sod on which we tread, seeing or not.

Image: Albrecht Dürer, The Great Piece of Turf, 1503, watercolour, Albertina, Vienna

2. Caravaggio’s Death of the Virgin

And Mary said, “My soul magnifies the Lord, and my spirit rejoices in God my Saviour, for he has looked with favour on the lowliness of his servant…” (Luke 1:46-48 NRSV)

Last week, thinking about art, faith and the ordinary, we explored a work of art devoted to the lowly, unremarked life of a clod of earth. Today, we turn to an image of death. It’s by the most audacious, contentious and influential painter of the Baroque era, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio.

It is his vision of the death of the woman most highly favoured in Christian tradition – Mary, the servant and bearer of God. Caravaggio knew the rich artistic traditions, over centuries, of giving form and honour to the peaceful ‘dormition’ (‘falling asleep’) and glorious assumption of the Virgin into heaven. His death of the Virgin is firmly of this world, grounded in the communal life of the apostles, of ordinary women and men, shaken by their loss. It bears witness to what death looks like, and to what grief looks like. Mary’s stiff, swollen, lifeless body, clad in a simple red dress, has been laid out on something like a kitchen table. It looks like a sudden death, unexpected, accidental, even, in ordinary time. There are no angels, no upward gazes, no vision of ascent to a radiant heaven. Above the barefoot mourners there is only a solid, wood-panelled ceiling. A rich red curtain is drawn aside to reveal and to direct our gaze to the human drama. The barest wisp of a thin gold halo alone denotes Mary’s sanctity.

Beside the corpse sits Mary Magdalene, bent in deep sorrow. At her feet is a brass basin, for washing the body. We might remember the sorrow that once led her to that garden tomb, in another time, at dawn. The need to be near to that body too, to anoint and to touch it. This basin is a humbly domestic echo of the alabaster jar of ointment that is, in art, the apostle’s traditional attribute.

The body laid out has borne God. It is a body that has known life in all its fullness, including incalculable grief. If we believe the stories that caused outrage in his own time about the models used by Caravaggio (prostitutes, drowning victims, pregnant women) then it is also a lowly and unknown Italian woman’s body that has known life and suffering of its own. Commissioned for a church setting in Rome, the painting’s stark realism proved unacceptable. Yet, as well as the audacity of an artist challenging all prior convention, there is reverence in this image. It is not reverence for splendour, for power or even for decorum. It is reverence for God’s dwelling among us. For the love, compassion and care human beings are capable of when they bear and raise children, when they grieve together or alone, and when they consent to their ordinary lives being transformed, utterly and forever, no matter who they are.

Image: Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Death of the Virgin c. 1601-6, oil on canvas, Louvre, Paris

3. Paula Modersohn-Becker’s Old Poorhouse Woman with Glass Ball and Poppies

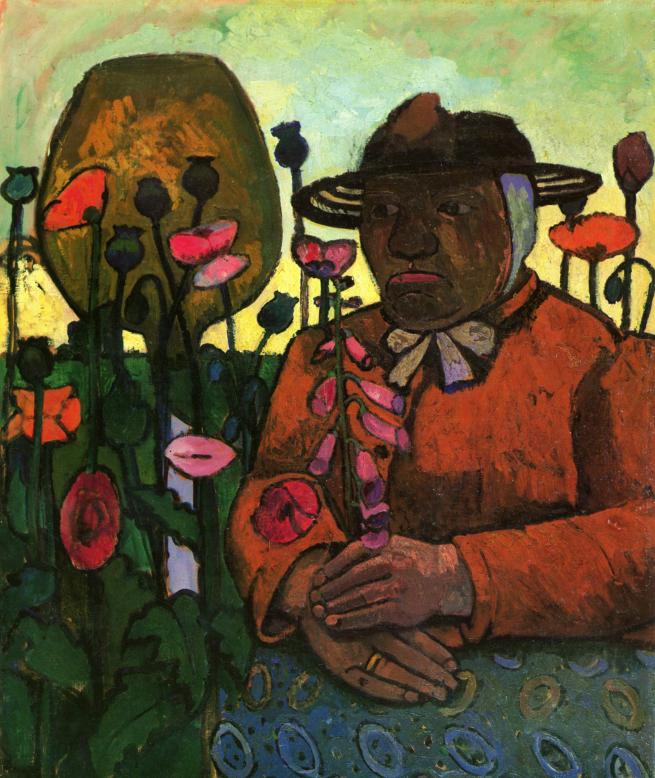

What does it mean to live attentively? How might looking at the overlooked enrich us? What can we learn from artists about intimacy with God and with others? In the middle of this month of ‘ordinary time’, as in the Northern hemisphere the light dwindles, let’s consider a work of art dedicated to an unremarkable, elderly, impoverished woman in a rural province. Paula Modersohn-Becker painted it in the last year of her short life, in 1907, in the small, north German village of Worpswede. She had joined a remote community of artists there, all drawn to the landscape of marshes and birch woods, and to the idea of simplicity. Her subject is a woman of the local poorhouse.

The old woman sits in a garden at dusk. Set against the remains of the day, her face and body are almost in darkness. The sun has sunk below the horizon. No longer illuminating brightly the things of the world, instead it offsets with unusual clarity the silhouetted shapes of the garden. Poppies are in flower, others already bulbous with seeds. We see the shape echoed in a large glass ball – something found commonly in peasant gardens there. The woman holds some picked foxgloves and a poppy. The flowers have connotations of death at the same time as they remind us of the beauty and transience of life. The poet Rainer Maria Rilke visited Worpswede many times. He wrote there of being mysteriously moved by ‘the intense colours which persisted without the sun’ and found in the plants and animals ‘a quiet and durable form of love and longing’.

The portrait tells us something of rural poverty in our modern time. But it also connects us with the ways people have long honoured one another. Immersing herself in both modern and ancient art over years spent in Paris, Modersohn-Becker went repeatedly to the Louvre Museum. There she discovered ancient Egyptian mummy portraits from the Roman era. These painted panels convey the unique humanity of those distant people even today and inspired her too towards a portraiture of radical authenticity.

Modersohn-Becker was drawn to the unremarked people of this obscure place: above all, to its children, its rural women and the very poor. She spoke of what she called their ‘biblical simplicity’. She painted them incessantly, not as a tourist looking for the exotic, nor as one of them, but as one who witnessed to their lives and took seriously the long work of looking and looking again.

What do we see? Do we see only the fading of a poor, failed, or unremarkable life? There is no halo of sanctity or specialness around this woman. She is surrounded only by those ‘durable forms of love and longing’. Modersohn-Becker said she was striving for ‘the utmost simplicity united with the most intimate power of observation’. Perhaps we can see with her that with embellishment or sentimentality stripped away, we can find the extraordinary after all in what is very ordinary indeed.

Image: Paula Modersohn-Becker, Old Poorhouse Woman with Glass Ball and Poppies, 1907, oil on canvas, Museen Böttcherstrasse, Bremen

4. Corita Kent’s that they may have life

I came that they may have life, and have it abundantly. John 10:10 (NRSV)

What could be more commonplace than our daily bread? Or, in an age of industrialised food production, the throwaway packaging a sliced white loaf comes in? This week, as part of our thinking about art and faith in ordinary time, let's consider a work that takes these lowly elements and does something transformative with them.

ENRICHED BREAD. The bright slogan and the graphic polka dots surrounding it are drawn from the wrapper of a product ubiquitous across the United States: Wonder Bread. This early piece of Pop Art, made in 1964, uses silk screen printing to explore playfully the connotations of the miraculous around this modern ‘wonder’ of sliced bread, ‘enriched’ with added nutrients. Its creator, Sister Corita Kent, was an artist, a nun, an activist and a ceaseless innovator. She ran the vibrant and often controversial art department at the Immaculate Heart College in Los Angeles, California. Nothing was too lowly to be turned into art – cardboard boxes, pop songs, advertising slogans or news headlines. And nothing was too holy to be voiced in the language of the streets and the marketplace. Here was art in celebration, protest against injustice and witness to the potential in even the most overlooked forms and marginalised people.

Look more closely. What wealth, what ‘enrichment’ could there possibly be in these impoverished materials? The work’s title is that they may have life (in ordinary lower case). It is a fragment of a pivotal statement of Jesus about himself, from the gospel of John. There are thirteen white discs, like hosts, communion wafers. One for everyone at the disciples’ table. There are circles of red, like drops or cups of wine, or blood. In them are traces of speech, handwritten. Words from a contemporary report on poverty quoting a Kentucky miner’s wife: ‘It's bad you don't know what to do when you've got five children standing around crying for something to eat and you don't know where to get it…’ and words from Mahatma Gandhi: ‘There are so many hungry people that God cannot appear to them except in the form of bread.’ They connect humanity’s need across the world with the man who came, blessed, broke, and gave bread as he prepared to lay down his life for his friends.

Corita Kent had no fear of contact with what is mass-produced, ordinary, commercial, cheap. On the contrary, in the lowly, the despised, even, she found joy, hope, and meaning, signs of God – in abundance. Here and now, among us. This cheerfully off-kilter print brings the bread of life into the world of real hunger. And into lives of false satiety. We might be surprised to be ‘enriched’ by the aesthetic and spiritual poverty of the supermarket aisle. Maybe the work is telling us something about the consecration of the world. That we may have life.

To learn more about Corita Kent and her work, please visit the Corita Art Center (to whom grateful thanks for their assistance).

Image: Corita Kent, that they may have life, 1964, serigraph, 38.75" x 30", Image courtesy of corita.org

5. Nadia Kaabi-Linke’s Flying Carpets

Reflecting on art, faith and ordinary time this month, we have been turning our gaze, with artists, to what is commonly ignored, overlooked, or even disdained. We’ve found the wonder in a muddy clump of weeds. We’ve considered the humanity of Mary the Virgin in unidealized death, and of another impoverished woman at the twilight of life. And we’ve seen the sacramental in our daily (white sliced) bread. So it’s fitting to end with a work of art that connects us once more with the ordinary unseen – in our own time.

Flying Carpets is an intricate installation made of stepped, cage-like stainless steel shapes, suspended on many elasticated cords, so that they hover in mid-air above the viewer. It is by the Tunisian-Ukrainian artist Nadia Kaabi-Linke. The title evokes an image with a rich heritage in Middle Eastern, Asian and other literary traditions and a popular fantasy in many cultures – of adventure, freedom and magical power. Yet it is also a work the artist calls ‘documentary sculpture’, firmly grounded in contemporary material reality.

Kaabi-Linke was inspired to make this work on a visit to Venice. There, she noticed the many street vendors – unlicensed, illegal traders daily risking arrest and penalty to sell counterfeit ‘luxury’ goods on rudimentary rugs or sheets set out on a bridge popular with tourists, the Ponte del Sepolcro. Most were migrants who had crossed by sea from Africa, the Middle East or South Asia. Kaabi-Linke (aware of her own, different, personal history of migration) spent a week with them. She traced and recorded the outlines of the provisional placement on the bridge over the water of their ‘flying carpets’. She saw the disjunction between that romantic image and the harsh reality of the sellers using cloths so that when the police or other threats approach, they can quickly gather their meagre wares and flee (or ‘fly’).

The cold, metallic structure of the hovering sculpture is grounded in the data of these realities. Documenting symbolically each vendor’s presence, it witnesses with meticulous attention to the transient, overlapping, incessant yet unseen imprints of these lives. Its cage-like forms are eloquent. They also make visible conditions most prefer not to see in a city famed for its wealth, beauty and culture – the origins of which lie in centuries of trading with the East. By attending to something very meagre – illicit stalls so provisional they are barely a slip of fabric on the ground – Kaabi-Linke creates a poignant monument to human lives of need and constant displacement.

The work alerts us to the daily, ordinary state of ‘flight’ in which too many people live. We might also consider its relationship with the appetites we seek to assuage with ‘luxury’ goods and ‘exotic’ travel. Rather than seeking spectacle in life, in art or in faith, perhaps the ordinary and the humble, right before us, is where we can most clearly trace the extraordinary connectedness of all humanity, all God’s image – whether we have eyes to see or whether we look away.

To learn more about the making of this work (and another), watch this five minute film of the artist talking about its story and origins.

Image:Nadia Kaabi-Linke, Flying Carpets, 2011, Stainless steel and rubber, 420 cm x 1300 x 340 cm, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Guggenheim UBS MAP Purchase Fund, 2015

Installation view: But a Storm Is Blowing from Paradise: Contemporary Art of the Middle East and North Africa, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, April 29–October 5, 2016. Photo: David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York.

Dr Deborah Lewer is Senior Lecturer in History of Art at the University of Glasgow and a regular speaker, consultant, author and retreat leader in many church contexts, including at her home cathedral of St Mary’s in Glasgow.