The East India Company and the monuments at St Paul's

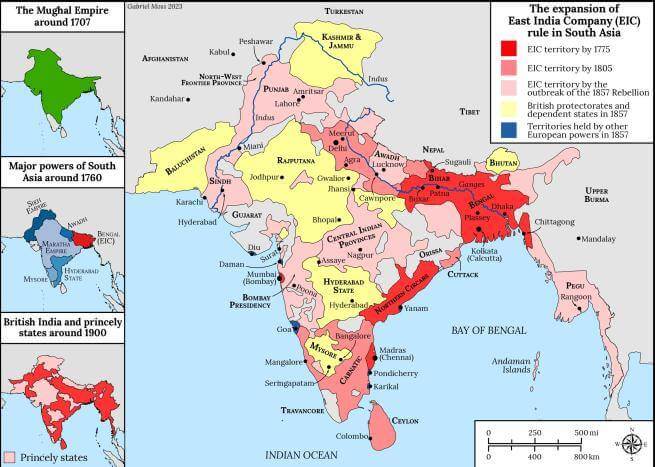

Map of the East India Company in South Asia by Dr Gabriel Moss.

'The parish church of the British Empire'

This well-known description of St Paul’s Cathedral, made by Canon Sidney Alexander in a sermon preached during the First World War, is visibly expressed in the monuments, mosaics, banners, and chapels on the Cathedral Floor and Crypt which relate to Britain’s imperial activities. Initially, a small set of monuments were erected to commemorate leading figures in the worlds of social reform, art, and literature. But, over the course of the 18th century, the naval battles which secured Britain’s rising global power produced a large number of national heroes, prompting the proliferation of monuments to individuals whose military exploits enabled Britain’s imperial pursuits.

The story of Britain’s expanding colonial rule in South Asia, achieved through the military endeavours of the East India Company, can be told through such monuments. In the 17th century, the Mughal Empire was the most important power in the region. The 18th century saw the decline of the Mughal Empire and the rise of breakaway states (such as Bengal, Awadh, and Hyderabad) as well as the advent of new forces (the kingdom of Mysore and the empires of the Marathas and the Sikhs). All these regimes were cash hungry because of their administrative and military ambitions, and so deeply interested in the tax revenues that international trade could bring. This brought them into conflict with the British East India Company, which traded in high value Indian and other Asian commodities such as spices, saltpetre, cotton textiles, silk, indigo dye, tea, and opium, and was keen to avoid paying taxes. The Company eventually defeated or subdued all these Indian regimes, and facilitated Britain’s lengthy rule over the Indian subcontinent, which eventually came to an end following struggles for independence. The partition in 1947 and the creation of two new states of India and Pakistan witnessed the biggest mass migration in modern history.

As the seat of the Bishop of London, St Paul’s Cathedral was connected to these developments. In the 1670s, the Bishop of London Henry Compton, who oversaw the rebuilding of St Paul’s Cathedral after the Great Fire, convinced the governors of the East India Company to only employ chaplains who had received a licence from him. And it was he, as the Bishop of London, who in 1680 gave permission for the very first Anglican Church built by company merchants to be consecrated in Madras (Chennai). The Bishop of London’s jurisdiction over India appears to have been unclear, uneven, and inconsistent until the first Bishop of Calcutta was installed in the early nineteenth century. Nevertheless the Bishop and St Paul’s Cathedral served the guilds, merchants, and financial institutions within the Diocese of London, whose interests in international trade were closely linked to British military success. The Cathedral also served as a setting for services of petition and thanksgiving for campaigns overseas.

A model of an East India Company ship called Falmouth, built in 1752, weighing 499 tonnes and featuring 26 guns. Made by Stepney Community Trust for a previous project on the Company's sailing vessels and their technological and scientific evolution.

The East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was established in 1600 with a charter by Queen Elizabeth I granting it the exclusive right to trade in the East. To protect this trade, the Crown also gave the Company increasing powers to raise its own armies and fortify territorial possessions. The Company attempted to negotiate favourable trade deals with the Mughals as well as the newly-rising regional powers. It soon began involving itself in local politics, actively installing preferred individuals as figurehead rulers. The first major political intervention was Robert Clive’s victory over the Nawab of Bengal at the Battle of Plassey in 1757. The Company placed a nominal leader on the Bengal throne, thus bringing the province of Bengal under its control. A further victory in 1764 against an alliance of Indian powers led to the Mughal emperor granting the Company Diwani (taxation rights and associated legal jurisdiction) over the provinces of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa, an event portrayed in a famous painting by Benjamin West, commemorated in Artist’s Corner in the Crypt. Company rule proved to be destructive, causing among other things, a disastrous famine in Bengal in 1769-70. This led to the extension of British Parliamentary control over the Company’s government in India through the Regulating Act of 1773, which established a Supreme Court at Calcutta and the office of the Governor-General. The first two monuments connected to the EIC at St Paul’s – William Jones (Judge of the Supreme Court of Bengal) and Charles Cornwallis (Governor-General of Bengal) – illustrate the growing political and administrative functions of the EIC in Bengal, under the supervision of the British Parliament. The East India Act of 1813 renewed the Company’s charter on the condition that Christian missionary activity be permitted in the territory under its control, and Thomas Middleton arrived in 1814 as the first Bishop of the newly-created Diocese of Calcutta.

However, most of the monuments related to the East India Company at St Paul’s Cathedral point to the heavily militarised nature of the Company’s rule, largely commemorating army officers and commanders. The EIC armies comprised units of British soldiers who served alongside Indian regiments under British commanders. The monuments tell of key wars waged by the Company, spanning vast swathes of land in the Indian subcontinent. In southern India, Cornwallis commanded Company armies against the kingdom of Mysore, capturing the capital of Seringapatam (Srirangapatna) in 1792 and compelling its ruler, Tipu Sultan, to sign treaty terms favourable to the Company. During a further siege in 1798-99 Tipu Sultan was shot dead, his capital razed, and his kingdom divided among the East India Company and its local allies. Arthur Wellesley, the future Duke of Wellington, became the new Governor of Mysore, and then commanded war against the Maratha rulers, defeating them at Assaye to gain additional territory for the East India Company. In the Kingdom of Nepal, Robert Rollo Gillespie commanded Company forces against the Gorkhali army in the 1814-16 Anglo-Nepalese War, or the Gurkha War, which ended with the signing of the Treaty of Sugauli and the cessation of some Nepalese-controlled territory to the EIC. The Anglo-Afghan Wars were fought between 1839-42 in an attempt by the EIC to expand their territory into Central Asia to stave off Russian expansion – an event commemorated in the memorial to the Punjab Frontier Force. Charles James Napier made his name with a famous victory at Miani, which allowed the EIC to annex Sindh in modern-day Pakistan in 1843. Napier and Samuel James Browne were also involved in the Company’s annexation of the Punjab in the 1845-49 Anglo-Sikh Wars, during which Duleep Singh, the youngest son of Maharaja Ranjeet Singh, was removed and exiled to England. The EIC defeated the Burmese state ruled by Pagan Min, and annexed Rangoon, Pegu (Bago), and several other territories under his control, an event commemorated in the memorial to Granville Gower Loch. The EIC was also eager to bring Awadh (modern-day Uttar Pradesh in northern India) under its rule. Upon annexing it in 1856 and exiling the last Nawab, Wajid Ali Shah, to Calcutta, Henry Montgomery Lawrence was appointed chief commissioner and agent to the Governor-General in Awadh. During the same period, the British navy bombarded the coasts of China, frustrated by the resistance of the Qing emperors to open trade, and in particular, their refusal to import opium, a narcotic which the EIC produced in India. China’s defeat in the Opium Wars resulted in the opening up of treaty ports and the British acquisition of Hong Kong – conquests related to the memorials of Granville Gower Loch, Charles George Gordon, and Harry Smith Parkes.

The 1857 Uprising (alternatively referred as the Indian Mutiny or the First War of Independence) began initially as a rebellion among sepoys (Indian soldiers) of the East India Company army – partly due to the requirement to grease rifles using cow and pig fat, greatly offensive to both Hindus and Muslims – but also due to long-standing grievances. The soldiers’ uprising soon developed into civil rebellion across northern India involving petty and large landlords, deposed rulers, and thousands of peasants and townsmen. The events at Cawnpore (Kanpur) and Lucknow – both its siege by sepoys and the eventual ‘relief’ by British forces – are commemorated in the memorials to Henry Montgomery Lawrence, Robert Cornelis Napier, John Eardley Wilmot Inglis, and Charles Metcalfe MacGregor, among many others. British retribution after reconquest was unprecedented in its brutality. There were mass hangings of civilians, looting of cities and slaughter of citizens, and blowing rebels from cannons. William Howard Russell, a reporter with The Times, and considered one of the first modern war correspondents, was scathing in his report of the atrocities he witnessed, describing the British response as ‘a war of religion, a war of race, and a war of revenge’, and writing, ‘I believe that we permit things to be done in India which we would not permit to be done in Europe, or could not hope to effect without public reprobation’.

In response to the mutiny, Queen Victoria ordered a ‘Day of Humiliation’ to be held at churches around the nation. At St Paul’s Cathedral, a service of penitence and prayer was held on the 7th October 1857. An article in The Times describing the sermons preached that day makes it clear that the chief sin for which forgiveness was sought was not the atrocities committed in India, but neglect in spreading Christianity among the Indian population.

With the East India Company to blame for misadministration in India, the Government of India Act of 1858 vested all its territories in the British Crown. Many monuments tell the story of this transition under new civil servants directly representing the Crown in India rather than the East India Company, including Henry Bartle Frere, Richard Southwell Bourke, Henry Wyle Norman, Robert Montgomery, Patrick Grant, and others. The Company’s military regiments were absorbed into the British Indian Army, which continued to expand into the largest standing army in the world until 1916, serving in both world wars. The memorial to the British Indian Army Volunteers honours the British, Indian, and Gurkha soldiers who served in the armies of the East India Company and the British Indian Army.

Monuments for the public

In 1837, Queen Victoria backed her Home Secretary Lord John Russell’s request that the Dean and Chapter of St Paul’s consider opening its doors freely to the public, so that visitors might have access to the monuments for the purposes of instruction, encouragement, and moral refinement. As objects for public engagement in today’s age, however, the Cathedral’s monuments present challenges. The art and inscriptions emphasise the military and political achievements of individuals who consolidated and expanded Britain’s power in the Indian subcontinent, and some monuments depict Indian people in a posture of subservience and deference.

Our community partnership project presents the shared history between Britain and Asia in several ways. Firstly, the explanatory texts about monuments to key individuals associated with the East India Company’s history in South Asia have been authored by those who have ancestral roots in the region. Secondly, the group of authors have tried to shift the spotlight onto characters forgotten and stories untold. The logo for this project, conceived by the group of authors and produced by a designer from India, brings together the many Asian figures who serve as the mere backdrop in these monuments, but who should be acknowledged in their own right. Thirdly, St Paul’s Cathedral has funded a social empowerment project to enhance the work of Stepney Community Trust to address issues of equality, belonging, and heritage within the British Asian community. Ultimately the project tries to direct public attention to communities from the Indian subcontinent whose histories and lived experiences are inseparable from the monuments you see here.

Many of the historical themes discussed by the authors in this trail – colonialism, occupation, forced migration, power imbalances, erased narratives, partition and violence – reverberate around the world today. Improving public understanding of history is important to better explain the past and shape our common futures.

The East India Company at St Paul's

Explore the full digital trail produced in collaboration with Stepney Community Trust.