Caribbean history and St Paul's Cathedral

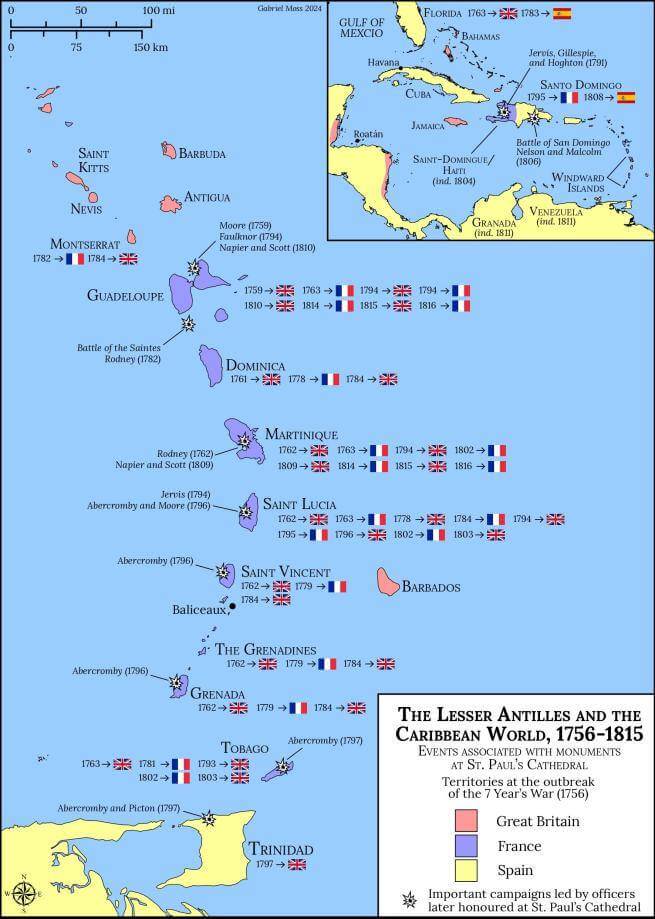

Map of the Lesser Antilles and the Caribbean world, 1756-1815: Events associated with monuments at St Paul's Cathedral, by Dr Gabriel Moss.

Caribbean history and St Paul's Cathedral

Only a small set of monuments stood initially at St Paul’s Cathedral. But Britain’s involvement in decades of near-continuous warfare with France during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries led to the dramatic proliferation of military and naval monuments. The officers who feature on this trail were primarily commemorated for their victories or deaths fighting the French at places such as Sudan, Egypt, Copenhagen, Portugal, Waterloo, and Trafalgar. But Britain’s intense quest to dominate the Caribbean islands, made rich by the labour of enslaved people, is a central — and much neglected — part of the stories behind the monuments.

This trail produced in collaboration with SV2G tries to make the Caribbean islands visible and humanise the lived experiences of the people along several themes: displacement, diaspora, and the spirit of resistance and uprising. The logo portrays the victims of the transatlantic slave trade; a black soldier recruited to serve the British in the 8th West Indian Regiment; and a number of freedom fighters featured in this trail, namely chief Joseph Chatoyer, Louis Delgrès, the Mulatto Solitude, and the Nanny of the Maroons.

The history of the Lesser Antilles does not begin with the expeditions to the Americas by European explorers at the end of the fifteenth century. Until at least the end of the eighteenth century, the indigenous people of the region also shaped the geography, economy, and civilisation of these islands. The expansion of European powers into the Lesser Antilles during the seventeenth century began a period of intensive rivalry for control and colonisation in the region. Increasingly marginalised indigenous people were removed from their lands through territorial acquisition which involved surveying and dividing up their lands, mounting attacks. and making ‘peace treaties’. Today, the indigenous culture of the region survives in the people, language and culture of these islands, and traces of the multiple occupations by Western powers are still to be found in the names given to indigenous people, places and streets.

From the mid-1600s, the economic value of the Caribbean became increasingly apparent to European powers, especially with the introduction of sugar as the preeminent commodity, along with tobacco, coffee, cotton, ginger, rum, salt and indigo. Labour-intensive cultivation was required to develop the tropical agriculture, and various European powers fought indigenous populations in order to establish slave economies. Between 1500 and 1800, approximately 12.5 million Africans were captured, trafficked, and sold as chattel (personal property) in the Americas and the Caribbean. On plantations, a hierarchical system based on qualification, gender, skin colour and birthplace was used, while plantation owners enjoyed their growing wealth, many from back home in Europe. Enslaved field workers, the majority of the enslaved African population, were either born in the colonies or had newly arrived. They were supervised by ‘drivers’, usually black enslaved men, who reported to ‘overseers’ who were usually white or free people of colour. Free people of colour included black or mixed-race enslaved people who had been freed, their descendants, and indigenous peoples; they did not have the same status as the enslaved Africans, but neither did they enjoy the legal rights of people recognised as white people. Self-liberated, formerly enslaved individuals known as Maroons made efforts to live independently in forests beyond cultivated land, away from authorities, and led numerous uprisings against Western attempts to occupy the islands. Among the many male maroons, the names of some women who led resistance are also known, including Breffu on the island of Saint John, Solitude in Guadeloupe, Flore Bois Gaillard in Saint Lucia, and the Nanny of the Maroons in Jamaica.

'A private of the 8th West India Regiment, 1803', National Army Museum, artist unknown, oil on canvas, c. 1803, National Army Museum.

War and resistance

The group of islands located in the Eastern Caribbean and comprising the southern islands of the Lesser Antilles held not only productive but also strategic significance, guarding the entrance to the Caribbean Sea and serving as a gateway to lucrative trade routes. Europeans named them the ‘Windward Islands’ based on the navigational term referring to ‘trade winds’ (east-to-west prevailing winds) which assisted sailing ships coming from Europe. When a series of major wars broke out in the eighteenth century involving European rivals, the Windward Islands became a key battleground in the struggle between Britain and France for control over this vital region.

During the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763), the inhabited islands of Martinique, Guadeloupe, Dominica, Tobago, Grenada, Saint Lucia, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, which had been called by different names by the indigenous populations (for example, Hairouna and Yurumein for Saint Vincent), were repeatedly fought over by Britain and France. The constant changing of hands caused great tension between the indigenous inhabitants and the European powers. The Caribs (the Kalinago and Garifuna people) fought the First Carib War (1769-1773) in response to British attempts to extend their colonial settlements into Black Carib territories and establish control over the islands of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines (Hairouna/Yurumein). A 1773 peace agreement delineated boundaries disproportionately in favour of the British. Caribbean islands were also a battleground in the War of American Independence (1775-1783): while Britain lost its American colonies, it gained control of Grenada, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Dominica, Saint Kitts, Nevis, and Montserrat. George Rodney’s victories made him a much-celebrated figure back in Britain. Black, indigenous, and mixed-race soldiers and sailors were active in these conflicts, serving on all sides.

The French Revolution which began in 1789 proclaimed liberty, equality, and fraternity, undermining traditional colonial authority and inflaming mutinies. Enslaved and free people of colour joined military factions on all sides of the conflict in exchange for the promise of freedom and increased rights. The desire for military and commercial dominance in the Caribbean, and its fear over the unrest caused by revolutionary principles, drove Britain’s campaigns during the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802) against the French and against indigenous peoples, enslaved Africans, and free people of colour. John Jervis, Robert Gillespie, and Daniel Hoghton had all been sent to the Caribbean to suppress rebellion by the enslaved population in Saint-Domingue (modern-day Haiti) in 1791. Although these efforts failed, John Jervis, together with Charles Grey (later the 1st Earl Grey), led successful campaigns in Martinique, Saint Lucia, and Guadeloupe in 1794 using a combination of regular British troops, local militia, and enslaved Africans whose freedom had been bought by the British in exchange for military service. Guadeloupe was placed under the governorship of Thomas Dundas, while Robert Faulknor was killed in action off the island’s coast. John Jervis and Ralph Abercromby invaded Saint Lucia at the request of white plantation owners when enslaved people began abandoning their estates, and John Moore became the island’s governor. Abercromby’s forces then fought rebels led by Julien Fedon in nearby Grenada, and suppressed the revolt in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines by indigenous people under their chief Joseph Chatoyer. Abercromby’s forces also captured Trinidad from the Spanish, and Thomas Picton was appointed the first British governor of Trinidad in 1797.

The Treaty of Amiens of 1802, negotiated by Charles Cornwallis with Napoleon Bonaparte, marked the end of the French Revolutionary Wars, but peace only held for ten months before the outbreak of the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815). Pulteney Malcolm won a celebrated victory at the Battle of San Domingo in 1806. Charles Napier and James Scott helped mount further invasions on Martinique in 1809 and Guadeloupe in 1810. Arthur Wellesley’s victory at Waterloo in 1815 ended the Napoleonic Wars.

Impact and legacies

The French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars claimed millions of lives. Families were separated, children orphaned, and turmoil created in the lives of ordinary people. During this period, people of all races and positions fought on all sides of the conflicts. Alongside white British, French, German, Dutch, and Spanish officers, black and mixed-race soldiers of all backgrounds (runaway enslaved people, or free men of colour who were sometimes enslavers themselves) chose which side to fight on, depending on their chances of survival, political persuasions, economic needs, and personal interests.

French laws granted equality to free people of colour in 1792 and abolished slavery in 1794, although Napoleon reversed this in 1802. Chattel slavery was finally re-abolished in France in 1848.

The British rejected French revolutionary principles and reinstated chattel slavery in the islands they conquered. But they also recognised the freed status of soldiers who had fought in the conflicts. Many of those captured by the British as prisoners of war were transported to Portchester Castle in England; some were formerly enslaved who had worked on French and British plantations, and others were from the free black and mixed-race communities. The British Army was the largest single purchaser of enslaved Africans in the Caribbean, buying their freedom in exchange for military service. Over 13,000 enslaved men and boys were purchased for immediate military service in the area from 1795 to 1808. The 1807 Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade made all trading of chattel slavery by British subjects unlawful, and the British West Africa Squadron was established in 1808 to stop illegal slave trading activity. However, chattel slavery itself had not been outlawed, and many remained enslaved in British colonies in the Caribbean. In 1833, Parliament passed the Slavery Abolition Act: children under the age of 6 were immediately freed, the rest became apprentice labourers bound to work for several years without compensation as a transition to freedom, and full freedom was granted to all former enslaved Africans on 1 August 1838, a day which many nations celebrate as Emancipation Day. Compensation of approximately £20 million was paid to former enslavers by the British government.

Labourers were needed to replace the enslaved workforce. By way of the indenture system, workers (initially from India and then from many other nations) travelled to British colonies in the Caribbean, signing a contract for several years of labour on small salaries under harsh conditions.

Although the events described here took place over 200 years ago, the physical legacy of warfare is still apparent in the forts and cannons that dot the islands, and in the languages and names still in use. The Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea were not just an arena for the British to showcase its naval supremacy: it was also the place of displacement, dislocation, enslavement, and death, for millions of enslaved, free, and indigenous people of colour. The trauma of multiple occupations and enslavements is still carried by the people of the Caribbean today. We are only at the start of the journey toward centring the Caribbean voice in the Revolutionary Wars. The campaigns have traditionally been documented without a focus on the impact on local populations. Although the archival records offer limited information and this area of historical study is under-developed, our project raises awareness about the activities of the British campaigns in the Caribbean and their lasting legacies, and introduces visitors to a number of Caribbean heroes.

War and resistance in the Caribbean

The monuments at St Paul's

Explore the full digital trail produced in collaboration with SV2G.