Our Restless Hearts: Four Reflections on Saint Augustine

Our Restless Hearts: Four Reflections on Saint Augustine

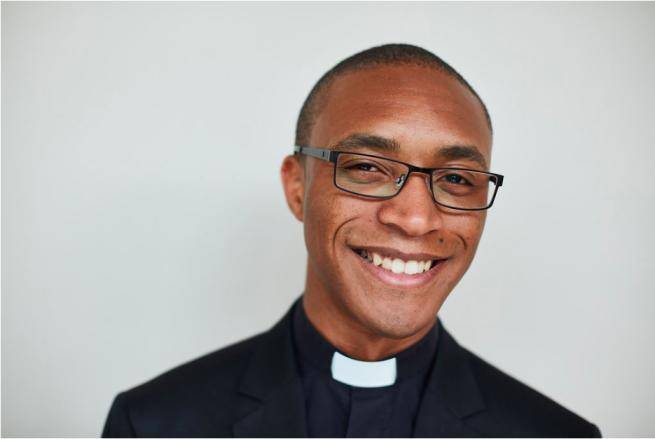

Jarel Robinson-Brown reflects on the lives of the Saints, particularly through the life of St Augustine, and what they can teach us about being holy and truly human.

1. St Augustine: an African Saint

The greatest early Christian thinkers were almost all African. One of the best known among them is St Augustine. And, because African History is Christian History, there is no better time to reflect on the contribution of African theologians to the life of the Christian Church than in October, Black History Month. In these reflections I want to help us think about the lives of the Saints particularly through the life of St Augustine.

Just last month I went to see for the first time the ancient ruins of Carthage in modern day Tunisia, a site where some of the earliest Christian martyrs gave up their lives for their belief in Jesus Christ and where some of the earliest texts on prayer were written. Carthage is not all that far from another North African site, Numidia, the birthplace of St Augustine.

Born on 13th November 354 Augustine was born to a pagan father and profoundly Christian mother. He grew up alongside two siblings and after learning grammar he went in about 370 to study rhetoric in Carthage. He grew up to become Bishop of Hippo on the coast of modern-day Algeria where he served from 395 to his death in 430. His writings are some of the most influential and indeed beautiful texts on the spiritual life we have inherited.

From the earliest days of the Church, Africa has been a major centre of Christianity shaping the church’s beliefs, preserving its most important documents and establishing and holding in creative tension a diversity of traditions.

People may argue about how African Augustine was but what we cannot argue about is his humanity. He stole pears in his youth, never wanted to be a priest, deserted the mother of his child, struggled to control his sexual lust, and was wracked by grief and shame for much of his life – in other words, he was a real human being with the capacity to teach us true humanity.

2. To seek the God who seeks us

I have never seen God. The closest I have come to seeing God is seeing him in the lives and faces of those whose lives have reflected the mystery that God is. Like the best of Saints, Augustine forces us to focus on God at work in our lives – he leads us to focus on our interior life, and to ask what I think is surely the deepest and most pressing question of our spiritual lives: ‘how does the mystery of who I am relate to the mystery that God is?’ For Augustine, a whole life appeared to have been spent seeking an answer to this question.

It has always been a comfort to me that Augustine’s life was one of multiple conversions, even beyond his baptism by St Ambrose in Milan at the Easter Vigil in 387. Augustine was a real human being and his was a humanity not washed away by the holiness he sought.

As I get older, I begin to think that the hardest thing to do as a Christian, is to embrace the fullness of my humanity. Sometimes I wonder if this is why I feel I know St Augustine less than most of the early Christian writers – that there is something in me that, out of fear, resists embracing Augustine as he truly is. Saints of course, are not called ‘Holy’ because they are perfect – there would be fewer, or no Saints if that were the case.

Rather, Saints are called Saints because they hold in a beautiful tension that paradox, troubling and bewildering to us perhaps, between being totally flawed yet still faithful. This is I think the true call of Christianity – to seek the God who seeks us – not in an imaginary perfect future where we have mastered the art of holiness, but a God who seeks us in the messy and imperfect deep of this present life, in the shaking, messy, guilt-ridden abyss of the human heart.

3. To Live in the Fullness of Life

Augustine loved his mother, Monica - but he soon learnt that he could not be like her. To Augustine, she was the model Christian, the very emblem of faithfulness, the one who embodied a Christian faith that he could not deny had value and actually worked. Her death absolutely shook his soul and he speaks about how painful it was to have their bond suddenly torn apart, and how watching her last breath evoked something of the child in him.

Augustine speaks often of wounds in his most popular work ‘The Confessions’ saying at one time of his encounter with God: ‘In my deepest wound, I saw your glory…and it astounded me’. The one place in Augustine’s life where he thought God could not be, was the place in which the glory of God resided.

Saints are a bit like stained glass windows. The light of God shines through them and falls, in various colours, upon our lives. None of us are called to be the light itself, because that is the Trinity – God: Father, Son and Holy Spirit. But we are invited to seek the light which the saints reveal to us.

The invitation of the Church – to come and live in the fullness of life, to bask and be changed by the light of God - is an invitation, I believe, to come and be fully human, not less human. We learn of course, as these reflections conclude, that this invitation is an invitation into a very real and mysterious death. Augustine, in his most vulnerable moments, doesn’t discover exactly who God is, rather he comes to know who and whose he is – known and beloved by God – flawed, human, and still infinitely precious. He would never be his mother, but then again, he was never called to be.

4. The Road to Eternity

All of Jesus’s disciples were utterly confused by following such a great and wise man who was, at least as they saw it, content to lay down his life on the cross. The Gospels show us their confusion as the penny drops more and more that the one they are following, who they have left all the knew to follow, was ultimately going to be nailed to the cross. One by one, the same disciples who were adamant that Jesus should not die, in the end, lay down their lives for what they had seen and known, heard and touched in the life, death and resurrection of Jesus.

In baptism, the key Christian symbol of new-birth, what we actually do is enter the depths of this darkness – enter the tomb and desolation that Jesus entered. There, in the deep waters we leave behind Adam and Eve drowning and we are clothed in Christ. We say in the Church that water is thicker than blood – meaning that what makes us one family is not that we share a surname or that we have the same DNA, but that we share in our identity as those who have been through the deep waters of baptism and are now on the road to eternity.

The true secret to Christianity – something that Saint Augustine and all the African saints knew – is that Christianity is about walking the way of the cross, and turning our back on the power of Empire. The invitation to follow Jesus is an invitation to embrace all that Jesus promised. The only life there is is the life that seeks the One who makes life possible. Augustine found in Jesus the end to all his longings but it cost him everything, as it did the disciples. Augustine invites us now, to pray with him in his own words and to learn the truth of this deep mystery that is God:

“You have made us for yourself, O Lord, and our heart is restless until it rests in you.”